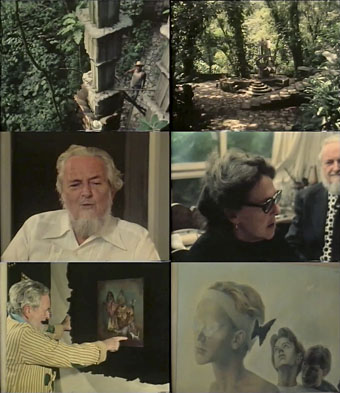

Ima ljudi koji nakon što popiju dobru kavu u restoranu mahnu konobaru i kažu mu "Naplatite mi kavu i cijeli restoran. Kupujem ga." Što bezobrazno bogati učine s novcem? Rijetko koji od njih bude toliko pametan da golemo nasljedstvo ulupa "u umjetnost". Edward James (1907 - 1984) bio je mecena nadrealista (osobito Dalíja, Magrittea i Leonore Carrington), nakladnik, loš (nadrealistički) pjesnik i izrazito zanimljiv čovjek - (u doslovnome smislu) graditelj snova: u Meksiku je kupio golemo zemljište i stvorio nadrealan vrt, nazvan Las Pozas, sa stubama koje ne vode nikamo itd. Evo ga, portretiranog na slavnoj Magritteovoj slici:

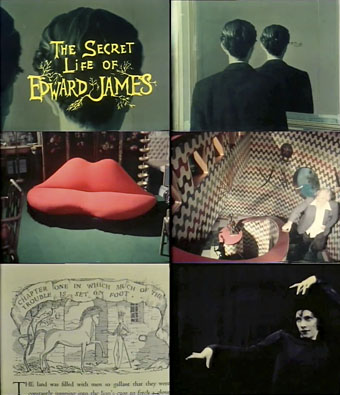

Dokumentarac, primjereno nazvana Tajni život Edwarda Jamesa otkriva sve što trebate znati o njemu, i nekoliko stvari previše.

A evo i o vrtovima:

At home with Edward James

...It’s a 1978 documentary concerning, and extensively featuring, Edward James, described by the narrator as “a legendary man most people have never heard of” and “the last of the great eccentrics”. That narrator, by the way, is no less a personage than jazz singer George Melly, of whom Quentin Crisp famously said “Mr Melly has to be obscene to be believed”.

Of course being “at home” with Edward James is a multinational undertaking. And people, what wonders the journey brings! James describes the travelling menagerie that is his life in the high, piping voice which contemporaries always remarked upon. His irascible temperament and bitterness are also much in evidence. There is little to contradict the impression that this hugely wealthy poet and patron was a victim of his ability to always get what he wanted.

His enormous inherited estate of West Dean is a case in point. Unhappy with his reputation as a collector and its attendant suggestion of dilettantism, James divested himself of an extraordinary collection of 20th century art and put the proceeds and the house at the service of a college. And yet we find him blithely trashing its pedagogical offerings on camera.

The entire panorama of James’s life is here: his patronage of Dalí and Magritte, his publishing ventures, the surreal interiors of his Lutyens-designed house Monkton and his marriage to Tilly Losch, including remarkable footage of the couple’s honeymoon in Hawaii. While James’s rancour about Tilly’s affairs and their subsequent divorce is still vivid, the documentary glosses over her counter suit accusing him of sleeping with men.

In Mexico City James checks into a hotel which allows him to keep (a lot of) live birds and catches up with artist Leonora Carrington, who died last year, then an amazingly youthful 70-odd. Naturally there is extensive footage of his estate in the town of Xilitla, where James was a combination feudal lord and cash cow. The nature of James’s later relationship with his factotum Plutarco, whose family he adopted as his own, is left to the viewer’s imagination. In any case this period seems to have provided the greatest happiness in a life which had no model of warm family life as reference.

Anyway, like I said, wonders. Enjoy!

The James Press

He fails every

conventional or generally accepted test of a good poet; yet he has a

freshness, he is worth taking seriously as a human being. - Peter Levi

James, born this day in 1907, established a pattern early on for his work. He was a prodigious correspondent, sending rambling letters to friends and enemies alike while conducting his chaotic business dealings – and writing poetry. He would colonise any flat surface in his vicinity as his paperwork spread. Once, when visiting a friend’s restaurant in San Remo before mealtime, said friend asked the poet to move his papers. Rather than clear up, James bought the restaurant.

As an adult James was never bound by the obligations of normal employment, or normal anything for that matter. With an inherited fortune under his belt he, in common with other artsy, dilattentish heirs and heiresses, took to verse (from the back pages of Strange Flowers alone we could cite Natalie Barney, Raymond Roussel, Nancy Cunard, Harry Crosby, Eric Stenbock and Evan Morgan). Their output often took the form of boutique limited editions which left bestseller lists untroubled, but Harry Crosby was Dan freakin’ Brown compared to Edward James.

Inspired by the Nonesuch Press, James at first hoped to produce deluxe editions of classic works, starting with a bilingual version of Goethe’s Faust, and he had already chosen Faustian Press as a name for his venture. However all that remained of these plans was a clenched fist (“faust” in German), the emblem for what would instead become The James Press. That self-identification is evident in the roster which featured the work of James himself (sometimes under an alias) with only one exception. But it was an impressive exception: Mount Zion, the first book of poetry by John Betjeman. The poet was listed as one of the quartet of directors along with James and a couple of aristocratic friends when the press was established in 1931.

After Mount Zion, James turned exclusively to luxury editions of his own works, each of which he grandly allotted an “opus” number. “Opus primum” was Juventutis Annorum, the first set of James’s poems (apart from a slim volume issued in 1926). The poet stored all but five copies of this book. This method became a pattern. Naturally James didn’t need to make a living from his writings, and the books he published were often works in progress, typeset and bound in luxury editions at more-or-less arbitrary points in their development, and it was his policy “to lay them by in my cellars as one lays up a stock of wine, to await for it to arrive at such a period when it can at last be reviewed in retrospect and drunk in that due state of mature fermentation which only the patient years give.”

A hugely prolific period ensued, a period which also coincided with James’s disastrous marriage to Austrian dancer Tilly Losch. James claimed that 1931’s Twenty Sonnets to Mary was dedicated to Mary, Lady Curzon, others claimed they were to a male friend; either way it was a strange gesture from a married man. Laengselia followed later in the year while 1932 brought Next Volume with illustrations by Rex Whistler (seen here), Carmen Amica and one of the most promising-sounding books: The Venetian Glass Omnibus. With illustrations by theatre designer Oliver Messel, it tells of a group of children travelling across Europe to Venice in a Baroque multi-levelled glass bus. That premise alone would seem to justify a greater print run than the 45 copies which eventuated.

In 1933, “Opus VII”, Your name is Lamia, offered a taste of trouble to come, Lamia being the cruel, beautiful creature of Greek mythology who lures and entraps men. The reference to Losch was clear.

This burst of activity came to a close in 1934 with Reading into the Picture. It was the same year that James divorced, publicly and bitterly. He accused Losch of infidelity while she countersued, citing James’s gay liaisons and naming dancer Serge Lifar as one of the men he had apparently slept with.

Edward James would continue to self-publish erratically until the late 1950s and continued writing until his death, but these books represent the core of The James Press’s small and eccentric output. They fetch hundreds of dollars if they come on the market at all, and a copy of Twenty Sonnets to Mary was recently on sale for USD 1400.

It is highly unlikely that anyone in the world has the full set of books under the James Press imprint. Lowe saw boxes of untouched volumes at West Dean, but that was over 20 years ago. It would be fascinating to know if they were ever released from captivity. Edward James’s outsize personality, the care that was evidently lavished on his printed works as well as their extremely limited runs ensures their value as bibliographic treasures. But that very rarity prevents us from judging the literary value of these elusive vintages. What can we say about his more readily accessible poetry?

The Heart and the Word is a commercially published (though now out out-of-print) sampler of James’s poetry, posthumously culled from the blizzard of paper he left behind. In his introduction Peter Levi admits “I am unable to discover any motive in his poetry that is not aesthetic”, and many verses do indeed suggest an avant-garde Basil Fotherington-Thomas touring the globe airily uttering “hullo trees, hullo sky” in leaden couplets.

To take some lines more or less at random: “Slow from the melting foothills draws the snow/where, islanded, the first green patches grow;/and through the rills and gorges of the hills/drips the long thawing by bluelidded sills.” Not terrible, but hardly life-changing and suggestive of nothing deeper than an enviably unhurried traveller’s fleeting impressions. Over the course of dozens of verses the weightlessness is wearying, though each reader will reach a different breaking point. It might be titles such as “To a primrose”, “The magic cuckoo calls her phantom word” or “Poor trees that cannot weep”. It might be lines like “Boisterous, shining, incorrigible puppy/who steals my shoe and hides it in the ditch,/it hurts to scold you when you are so happy,/angelic joy, distracted by an itch!”. Personally, the poem about Napoleon which rhymed “Jena” with “gainer” was the point at which I wanted to throw the book across the floor, remembering just in time that it was a library book.

Is this unfair, picking through a dead man’s discarded verse and passing judgment? Well, James chose to be remembered with the description “POET” on his self-designed gravestone, and recklessly opined that his verse would “burst upon an astonished world” after his death.

Perhaps it just needs to go back to the cellar for a few more years.

Surreal estate

Today we visit a masterpiece of al fresco Surrealism created by British poet and patron Edward James, who died on this day in 1984.

James was born in 1907 into a family with great wealth but little in the way of affection. One of his oft-told anecdotes has his mother dressed for church one Sunday, instructing the nanny to summon one of the children to accompany her. “Which one, Madam?” the nanny asked, to which she replied “Whichever goes best with my blue dress”. Packed off to boarding school, James was further traumatised by the harsh discipline and retreated into his own rich imagination.

Forever restless, James settled first in New Mexico, then went exploring in (old) Mexico, chasing whims and fantasies. It was in pursuit of a strange flower, specifically a rare orchid, that James first stumbled upon Xilitla, about 25o kilometres due north of Mexico City, high in the jungle covered mountains.

In 1947 he purchased 32 hectares and began

transforming the estate, a task which would occupy him for the rest of

his life and become his greatest work. Las Pozas (“the pools”), as it

was named, stands in a tradition of eccentric landscaping that includes

the gardens of Quinta da Regaleira in Sintra, Portugal and Park Güell

in Barcelona, designed by Gaudì. And like James, the original owners of

those properties (respectively, António Monteiro and Count Eusebi

Güell), were worldly aesthetes with the means and vision to create their

own fantasy worlds.

Las Pozas provided work for around 100 local workers, but James was an erratic foreman. He could be generous and affable, but he was also capable of despotic rages. An incident in which he was struck by a tree trunk rolled down a hill was, he believed, no accident. It left him reliant on a cane for the rest of his life.

It was a freak incident in 1962 which largely determined the current format of the garden. A rare snowstorm covered the slopes of Las Pozas and, most devastating for James, killed thousands of his beloved orchids. He decided to “plant” structures which could withstand any weather, and so now some 200 bizarre concrete forms dot the estate.

These constructions bore names straight out of the poet’s verse, like “Bathtub shaped like an eye” and “House with a roof like a whale”, and were sometimes painted in shrill colours by James himself. Just as the teeming jungle of Las Pozas can scarcely be called a “garden”, the word “folly” — suggesting whimsical structures on manicured English lawns — is unequal to the task of defining these enormous objects rising, half-dream, half-nightmare out of the jungle.

Since James’s death, however, the jungle has threatened to overwhelm even these hardy perennials, and a foundation was formed in 2008 to ensure that Las Pozas can be enjoyed by the next generation of oddity enthusiasts.

James and the giant artichoke

I ask little of my readers. But please, promise me this: if – through inheritance, games of chance or miraculous stock market windfall – you come into a large fortune, please spend it like Edward James and not David Siegel (or, y’know, go nuts with it and give it to charity or something…).

David Siegel, just so we may quickly dispatch him, is a Florida businessman who was bent on building this, a fist-gnawingly ugly pastiche of Versailles. The global financial crisis stopped work, which makes you realise that even a worldwide fiscal catastrophe has its silver lining.

English poet and sponsor Edward James, on

the other hand, now there was someone who knew how to blow his

considerable wonga on some seriously excellent shit. You may recall we

dropped in on Las Pozas,

his extraordinary Mexican estate to which he devoted much of his life.

But long before that, James – who was born on this day in 1907 – was

pioneering domestic Surrealism, as early as his university days when he

decorated his Oxford rooms with Roman busts wired up so that music

issued from their mouths.

Meeting

Salvador Dalí liberated the already generous bounds of James’s

imagination. He used his inherited wealth to bankroll the promising

young Spanish artist’s career, as well as working with him on Surrealist

objects for James’s homes. From this fruitful collaboration emerged

such iconic pieces as the lobster telephone and Mae West lips sofa.

Meeting

Salvador Dalí liberated the already generous bounds of James’s

imagination. He used his inherited wealth to bankroll the promising

young Spanish artist’s career, as well as working with him on Surrealist

objects for James’s homes. From this fruitful collaboration emerged

such iconic pieces as the lobster telephone and Mae West lips sofa. Working

with interior designer Syrie Maugham, James turned his Lutyens-designed

mansion Monkton House into a hypnagogic hallucination, a habitable

theatre set abounding in decontextualised body parts and other

amuse-oeils. A carpet preserves the wet footprints of his dog,

disembodied hands caress a light fitting and another Dalí piece is a

sight gag on the theme of “arm chair”.

Working

with interior designer Syrie Maugham, James turned his Lutyens-designed

mansion Monkton House into a hypnagogic hallucination, a habitable

theatre set abounding in decontextualised body parts and other

amuse-oeils. A carpet preserves the wet footprints of his dog,

disembodied hands caress a light fitting and another Dalí piece is a

sight gag on the theme of “arm chair”.

Drapery is a recurring theme throughout the

house. Usually used to soften right angles and deaden echoes, James uses

it to disorient and perplex. Plasterwork turns the inside out, while

his bedroom was swathed in funereal black velvet, inspired by Nelson’s

hearse.

One

of James’s most appealing projects was never realised. This strange

flower planned – appropriately – to build a strange flower.

Specifically, a pavilion in the shape of a giant artichoke (which is an

edible thistle, botany fans). While pleasingly daft, this 1936 design

was not entirely dissimilar to earlier works such as the 18th century folly, the Dunmore Pineapple.

One

of James’s most appealing projects was never realised. This strange

flower planned – appropriately – to build a strange flower.

Specifically, a pavilion in the shape of a giant artichoke (which is an

edible thistle, botany fans). While pleasingly daft, this 1936 design

was not entirely dissimilar to earlier works such as the 18th century folly, the Dunmore Pineapple.For something which was essentially an outsized entrée it had an impressive pedigree, designed as it was by Sir Hugh Casson, later responsible for shaping the architecture of the Festival of Britain, and Christopher Nicholson, who numbered a studio for Augustus John among his long list of projects. Sadly it was never realized, and James turned his attention to Las Pozas.

Incidentally someone has built a giant artichoke; disappointingly not in my home country, whose vast repertoire of big things doesn’t run to the leafy delicacy, but in California).

The Secret Life of Edward James

From the earliest days of YouTube there were two films about Surrealist art that I’d been hoping would one day be posted somewhere so I could watch them again. One was José Montes-Baquer’s collaboration with Salvador Dalí, Impressions de la Haute Mongolie – Hommage á Raymond Roussel (1976), which eventually turned up at Ubuweb; the other was Patrick Boyle’s The Secret Life of Edward James, a 50-minute documentary about the wealthy poet and Surrealist art patron that was screened once, and once only, on the UK’s ITV network in 1978. Boyle’s film, which was narrated by James’ friend and fellow Surrealism enthusiast, George Melly, was my first introduction to a fascinating figure who was one of the last—if not the last—of the many eccentric aristocrats that these islands have produced. I knew James’ name at the time from Surrealist art books where the Edward James Foundation was credited as the owner of paintings by Magritte and Dalí, but had no idea that James was the model for three of Magritte’s paintings, including La reproduction interdite (1937), that he’d abandoned his huge ancestral home to create a Surrealist house at nearby Monkton, and had also commenced the construction of a concrete fantasia, Las Pozas, in the heart of the Mexican jungle at Xilitla. Boyle’s film explores all of this in the calm and uncondescending manner that used to be a staple of UK TV documentaries. I’ve been telling people about this film for years, hoping that somebody might have taped it (unlikely in 1978) but no one ever seemed to have seen it.

In 1986, two years after James’ death, Monkton was up for sale so Central TV sent George Melly and director Patrick Boyle to revisit the place. Monkton, A Surrealist Dream, was the result, a 26-minute documentary which relied heavily on the earlier film to fill out the details of James’ life. The original resurfaced for me again, albeit briefly, in Brighton in 1998. A Surreal Life: Edward James (1907–1984) was an exhibition at the Brighton Museum & Art Gallery which featured many works from the James art collection, including major pieces by Leonora Carrington (who appears in Boyle’s film), Dalí, Leonor Fini, Magritte, Picasso, Dorothea Tanning, Pavel Tchelitchew and others. A tape of the 1978 documentary was showing on a TV in one part of the exhibition but the people I was with were reluctant to stand around for an hour so all I got to see was a minute or so of Edward in his jungle paradise. Happily we’re all now able to watch this gem of a film since it was uploaded to YouTube earlier this month (my thanks to James at Strange Flowers for finding it!).

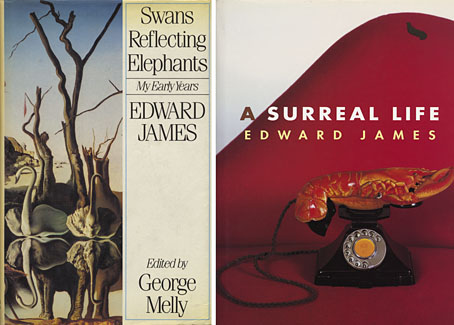

For anyone whose interest is piqued by all of this, two books are worth searching for: Swans Reflecting Elephants, My Early Years (1982) is an autobiography which George Melly compiled from conversations with its subject (and which apparently finished their friendship). James’ propensity for invention means it can’t always be trusted but then that’s the case with many memoirs. A Surreal Life: Edward James (1998) is the 160-page exhibition catalogue which explores James’ life and aesthetic obsessions in a series of copiously-illustrated essays. Both books can be found relatively cheaply via used book dealers.

Las Pozas panoramas

Photo by Carlos Ernesto Guadarrama Muñoz.

How soon things change. In 2006 when I wrote something about Las Pozas, the unfinished concrete fantasia constructed by Edward James at Xilitla in the Mexican jungle, there was little information about the place on the web. A couple of years later photos had appeared on Flickr and Monty Don had been there with TV cameras for the BBC’s Around the World in 80 Gardens. Now, thanks to 360cities.net, we have a collection of panoramic views inside James’ platforms, plazas and stairways to nowhere. See the complete set of views here.

Photo by Jose Luis Perez.

Edward James described himself as a poet (and is credited as such on his gravestone), but he’s far better known as one of the primary patrons of Surrealist art and a lifelong proponent of the Surrealist ethos, hence Las Pozas whose construction occupied him up to his death in 1984. In addition to being the model for Magritte’s La reproduction interdite (1937), James also converted Monkton, his home in England, into a Surrealist showcase. It’s a place I’ll be writing about at greater length when I find the time.

Photo by Jose Luis Perez.

In 1947 James began commuting regularly to Xilitla in Mexico (a country specially favoured by the Surrealists) and in 1949 began the construction of Las Pozas, a sprawling jungle folly that eventually developed into a cross between a sculpture park and a plan for a new school of Surrealist construction not far removed from similar flights of invention by Antonio Gaudí. Las Pozas occupied him up to his death and unfortunately remains incomplete like so many works of fabulist architecture. There is, however, a small site devoted to it here with some magazine features and details of how to find the place should you ever be on holiday in the region.

-John Coulthart

Xilitla:

http://www.junglegossip.com/

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar