Nova estetika je pojam koji je skovao umjetnik, dizajner i pisac James Bridle a odnosi se na sve veći prodor svega digitalnog u svakodnevni, fizički život i na njihovo postupno stapanje. Pikseli postaju nova ontologija. Nova estetika je i umjetnički pokret koji potiče ljudsku suradnju s digitalnim strojevima.

Priči je puno je pomogao Bruce Sterling svojim člankom objavljenim u Wiredu. Nakon toga uslijedilo je poveće teorijsko i umjetničko komešanje.

new-aesthetic.tumblr.com/

booktwo.org/

The New Aesthetic is a term used to refer to the increasing appearance of the visual language of digital technology and the Internet in the physical world, and the blending of virtual and physical. The phenomenon has been around for a long time but lately James Bridle and partners have surfaced the notion through a series of talks and observations. The term gained wider attention following a panel at the SXSW conference in 2012.

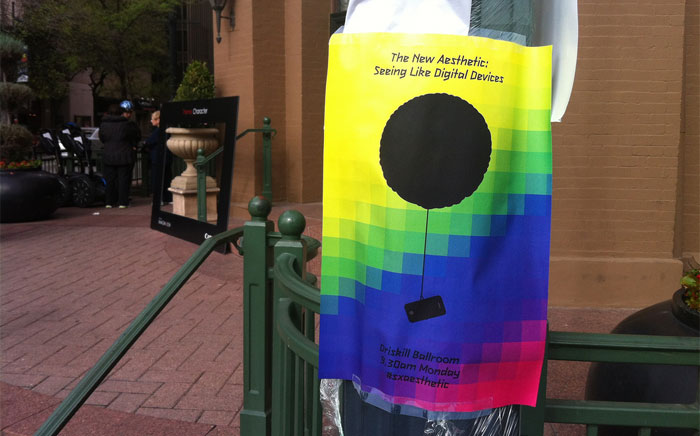

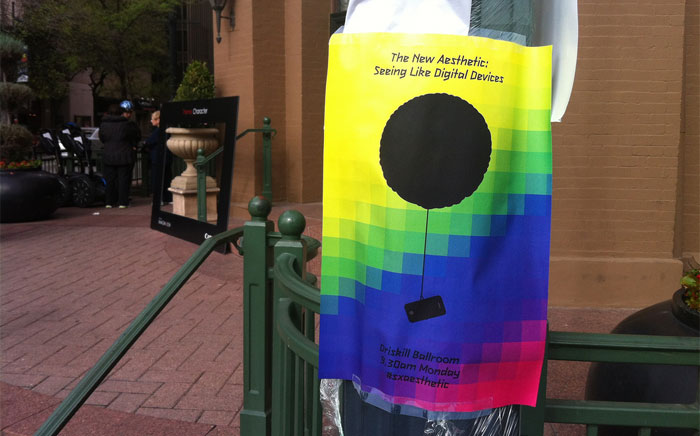

The New Aesthetic is a nascent art movement or collective that is documenting "eruption of the digital" and "revels in seeing the grain of computation". Developing from a series of collections of digital objects that have become located in the physical the movement circulates around a blog named "The New Aesthetic" and which has defined the broad contours of the movement without a manifesto . The New Aesthetic as a concept was introduced at South By South West (SXSW) on March 12th 2012, at a panel organised by James Bridle and included Aaron Cope, Ben Terrett, Joanne McNeil, and Russell Davies . What really propelled the ideas around the New Aesthetic into critical and public consciousness was an article written by Bruce Sterling in Wired Magazine, and which both described the main outlines but also proposed some key critical areas for development. The response from across the web has been rapid and engaged with a number of significant contributions already having been made

The author Bruce Sterling has said of the New Aesthetic:

- The “New Aesthetic” is a native product of modern network culture. It’s from London, but it was born digital, on the Internet. The New Aesthetic is a “theory object” and a “shareable concept.”

- The New Aesthetic is “collectively intelligent.” It’s diffuse, crowdsourcey, and made of many small pieces loosely joined. It is rhizomatic, as the people at Rhizome would likely tell you. It’s open-sourced, and triumph-of-amateurs. It’s like its logo, a bright cluster of balloons tied to some huge, dark and lethal weight.

- New Aesthetic is a collaborative attempt to draw a circle around several species of aesthetic activity—including but not limited to drone photography, ubiquitous surveillance, glitch imagery, Streetview photography, 8-bit net nostalgia. Central to the New Aesthetic is a sense that we’re learning to “wave at machines”—and that perhaps in their glitchy, buzzy, algorithmic ways, they’re beginning to wave back in earnest.

One movement that draws parallels to "New Aesthetic" is "Seapunk". - wikipedia

The New Aesthetic by James Bridle et al.

Central site:

new-aesthetic.tumblr.com;

James Bridle on the New Aesthetic:

riglondon.com/blog/2011/05/06/the-new-aesthetic;

Bruce Sterling on the New Aesthetic:

wired.com/beyond_the_beyond/2012/04/an-essay-on-the-new-aesthetic;

Responses to Sterling, defenses of Bridle:

thecreatorsproject.com/blog/in-response-to-bruce-sterlings-essay-on-the-new-aesthetic;

Also created by Bridle:

a seven-thousand-page book of all the changes to the Wikipedia entry

“Iraq War,” “Robot André Breton,” a semi-pornographic parody of the

IKEA catalog;

Other artists represented in the New Aesthetic:

Nicolas Nova, Jonathan Rennie, Adam Harvey, many pseudonymous Flickr contributors, 3-D printers, and Louis Vuitton;

Non-image content encompassed by the New Aesthetic:

collated news articles, robotically altered text, essays, Twitter feeds, videos

As fascinating as its name is bland, “the New Aesthetic” refers to a website launched in 2011 by the London-based artist, designer, and writer James Bridle; to the many images archived on that site; to Bridle’s argument about the sensibility that those images share; to the international panoply of pictures, websites, texts, and computer programs created in response; and to a heated debate about what they mean. The New Aesthetic instructs us to look to the future, but it might be most interesting for what it says about the recent past.

Put too simply, the New Aesthetic is an art movement, or an attempt to launch one, that welcomes human collaborations with real or imagined digital machines. The earliest pictures on Bridle’s site were either real objects that looked like crude programmed creations, or digital images whose oddball features put their difference from “real life” up front. Coarse green squares in an arid, tan landscape looked like early-’80s Atari graphics but were really “agricultural land seen from space.” A pendulous, blue-on-blue column of LEGO-like blocks, representing water, “poured” out from a New York City pipe. Later works included imaginary buildings shaped like QR codes, an essay about Auto-Tune, and much reuse of Google Street View.

In such vistas, to use Bridle’s words, “representations of people and of technology begin to break down… at the pixels.” We are already cyborgs, these images say, and we should know it; digital vision and computer-assisted perception have become so normal that we need new art to show how weird they can be.

Proponents cast the movement as anti-nostalgic, opposed to the idea that we are fake or artificial or compromised now but were real or organic or natural—and therefore more interesting or sympathetic—back then. Au contraire, the New Aesthetic says: we are as real as we have ever been, even though for us the real, the visible, the everyday involve so many algorithms and so many machines. Bridle says he wants to attack “the belief that authenticity can only be located in the past.”

And yet New Aesthetic images and attitudes also point to that past. Those blocky grid breakdowns, those crude maps and repurposed texts, invoke the 1980s and 1990s; once, these were the best computers could do, and it’s their very obsolescence that lets us register them as other than useful: as “aesthetic,” or as beautiful. With its eight-bit graphics, its cut-up grid patterns, its screens within screens within screens, the New Aesthetic reminds us that we have had computers and computer graphics, CGI and CAD, spy cams and Photoshop, for years. They have changed along with us; the digital, these works say, has its own history.

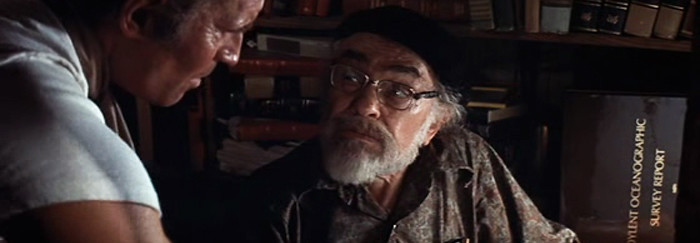

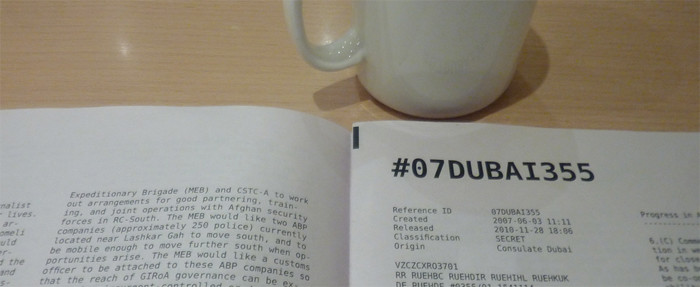

It’s easy to make the New Aesthetic political, seizing the high-tech

means back from corporate overlords—Bridle’s initial site included a

Google Maps image of the compound where Osama bin Laden died, along with

dresses based on “dazzle camouflage” from military ships and planes.

(The movement’s origin in London, perhaps the world’s most surveilled

city, is no accident.) But as a collection of images, and as

instructions for making more, the New Aesthetic isn’t just a

scramble-the-system protest, nor is it a claim about what watches whom.

It’s more like a claim about how we watch, a claim not just that we are

already data, acclimated to and dependent on our machines, but that we

have been so for a while. No wonder its finest examples look at once

startling, “dazzling,” and somehow not quite new. —Stephen Burt

New Aesthetic New Anxieties is the result of a five day Book Sprint organized by Michelle Kasprzak and led by Adam Hyde at V2_ from June 17–21, 2012.

Authors: David M. Berry, Michel van Dartel, Michael Dieter, Michelle Kasprzak, Nat Muller, Rachel O'Reilly and José Luis de Vicente.

Facilitated by: Adam Hyde

You can download the e-book as an EPUB, MOBI, or PDF.

EPUB: http://www.v2.nl/files/new-aesthetic-new-anxieties-epub

MOBI: http://www.v2.nl/files/new-aesthetic-new-anxieties-mobi

PDF: http://www.v2.nl/files/new-aesthetic-new-anxieties-pdf

Annotatable online version: http://www.booki.cc/new-aesthetic-new-anxieties/_draft/_v/1.0/preface/

The New Aesthetic was a design concept and netculture phenomenon launched into the world by London designer James Bridle in 2011. It continues to attract the attention of media art, and throw up associations to a variety of situated practices, including speculative design, net criticism, hacking, free and open source software development, locative media, sustainable hardware and so on. This is how we have considered the New Aesthetic: as an opportunity to rethink the relations between these contexts in the emergent episteme of computationality. There is a desperate need to confront the political pressures of neoliberalism manifested in these infrastructures. Indeed, these are risky, dangerous and problematic times; a period when critique should thrive. But here we need to forge new alliances, invent and discover problems of the common that nevertheless do not eliminate the fundamental differences in this ecology of practices. In this book, perhaps provocatively, we believe a great deal could be learned from the development of the New Aesthetic not only as a mood, but as a topic and fix for collective feeling, that temporarily mobilizes networks. Is it possible to sustain and capture these atmospheres of debate and discussion beyond knee-jerk reactions and opportunistic self-promotion? These are crucial questions that the New Aesthetic invites us to consider, if only to keep a critical network culture in place.

The blog of James Bridle: literature, technology and book futurism, since 2006.:

Top articles:

- 3/12 #sxaesthetic

The New Aesthetic goes to SXSW. - 12/11 The New Aesthetic: Waving at the Machines

Firing a laser through a cloud of ideas. - 10/11 The New Value of Text

There is an increasingly pervasive notion that other forms of media are additive to literature, that they somehow improve it. Because, you know, books are just telling stories, right? - 3/11 Seven posts about the future

Nostalgia, fiction, sharing and stories. - 17/2/11 Publishing Experiences

Why publishers should reconsider what they do. - 25/10/10 Network Realism

William Gibson and new forms of Fiction. - 5/10/10 Walter Benjamin's Aura: Open Bookmarks and the form of the eBook

The future of social reading. - 6/9/10 On Wikipedia, Cultural Patrimony, and Historiography

Visualising archives and historical process.

I’d always intended to talk about The New Aesthetic, but up until about the day before I didn’t really know how. The original title of the talk was “The Robot-Readable World”, but this didn’t really sit right with me; it’s one aspect of NA, for sure, but there was something else I wanted to emphasise: the human aspects and emotions of NA, and the becoming-human of the machines.

So the talk became “Waving at the machines”, a 50-minute, 120-slide vector through the idea, an idea that still seems massive and nebulous, but which it is possible to fire a laser through and illuminate some motes. I’m not sure I managed to phrase the camouflage stuff quite right, and the need for an ending always feels like a cop-out, but nevertheless, I cover many of the bases. (Web Directions have also transcribed the entire talk, should you be so crazy as to attempt to read it.)

For those of you who haven’t come across the New Aesthetic before, it began here, it continues here, I’ve been interviewed about it here, and here are a few responses.

The adventure continues; Kevin Slavin, Aaron Straup Cope, Ben Terrett, Joanne McNeil, and myself will be interrogating the concept at SXSW next year, and no doubt it will be covered elsewhere before then.

Huge thanks to everyone at Web Directions, particularly to Maxine Sherrin for all her help and patience, to Hunting With Pixels for the video, and to everyone who attended.

Recent posts from the blog:

- 5/9/12 Work is being done here

A short film about Happenstance. - 22/8/12 Coming to America

Teaching at NYU, Fall 2012. - 25/7/12 Frozen Moments

Art, photography, video and animation. - 24/7/12 The internet considered as a fifth dimension, that of memory

Ramblings on the subject of the network - 20/7/12 Balloon Mapping, Guimarães

Mapping the European Capital of Culture 2012 with helium balloons. - 13/7/12 Start-ups and Slash Fiction

Talk from NEXT Berlin 2012, on ways of making meaning and fiction online. - 11/7/12 Every Book I’ve Ever Made

My talk from the Do Lectures, Spring 2012. - 10/7/12 A Ship Aground

Observations from a Room for London. - 2/7/12 The overlapping consensus

Rawls, Jurgenson, Prickett, Krieder, duality. - 1/6/12 Recent work: GPS, Kindle and GIFs

Articles for ICON and Domus, and a GIF for the Photographer's Gallery. - 31/5/12 Mapping Workshop, Guimarães

Open mapping the European City of Culture - 23/5/12 Opinions are non-contemporary

I want to hear about it like I want to hear about your dreams. - 16/5/12 The dreadful luminosity of everything

On light. - 11/4/12 We Found Love In A Coded Space

Talk from Lift 2012, about the New Aesthetic, concerning literature, sexuality, and collaborating with the network. - 4/4/12 n/a (Pope Communique #1)

Network Realism -> New Aesthetic -> ? - 2/4/12 Writing in Newspapers and Magazines

Recent work for the Observer, WIRED and ICON. - 27/3/12 read/write

Attempting (and failing) to differentiate between things. - 15/3/12 #sxaesthetic

The New Aesthetic goes to SXSW. - 27/2/12 CERN

In which I am EXCITED about SCIENCE. - 22/2/12 Kaleidoscopic Permutations

Agency, history, software, politics.

New Aesthetic

http://new-aesthetic.tumblr.com/

The New Aesthetic is an ongoing research project by James Bridle.

Since May 2011 I have been collecting material which points towards new ways of seeing the world, an echo of the society, technology, politics and people that co-produce them.

The New Aesthetic is not a movement, it is not a thing which can be done. It is a series of artefacts of the heterogeneous network, which recognises differences, the gaps in our overlapping but distant realities.

It began here: www.riglondon.com/blog/2011/05/06/the-new-aesthetic/

Here is a talk (video) about the visual aspects of the New Aesthetic (here is a transcript).

Here is another talk (video) about the New Aesthetic, concerning literature, sexuality, and collaborating with the network.

Reports of a panel on the New Aesthetic at SXSW.

James Bridle — Waving at the Machines

transcript http://www.webdirections.org/resources/james-bridle-waving-at-the-machines/

http://rorschmap.com/ http://robotflaneur.com/

The New Aesthetic

For a while now, I’ve been collecting images and things that seem

to approach a new aesthetic of the future, which sounds more portentous

than I mean. What I mean is that we’ve got frustrated with the NASA extropianism

space-future, the failure of jetpacks, and we need to see the

technologies we actually have with a new wonder. Consider this a

mood-board for unknown products.

(Some of these things might have appeared here, or nearby, before. They are not necessarily new new, but I want to put them together.)

For so long we’ve stared up at space in wonder, but with cheap satellite imagery and cameras on kites and RC helicopters, we’re looking at the ground with new eyes, to see structures and infrastructures:

→ Guardian gallery of agricultural landscapes from space.

→ Updates on Bin Laden’s Death, New York Times

→ Tracking iPhone locations with iPhoneTracker, from Ben on Flickr

The map fragments, visible at different resolutions, accepting of differing hierarchies of objects.

→ Tracking iPhone locations (Ongoing personal project)

→ Landscape Permutation 2 (2010), David Semeniuk

Views of the landscape are superimposed on one another. Time itself dilates.

→ Three screens (for London 2010)

→ FER IN 1970 & 2010, Buenos Aires, Back to the Future Series, Irina Werning

→ Luminant Point Arrays, by Stephan Tillmans

Representations of people and of technology begin to break down, to come apart not at the seams, but at the pixels.

→ Diptych 1 on Flickr (ongoing personal project)

→ CV Dazzle by Adam Harvey

→ Megabytes of Spring, Reed+Rader for vmagazine.com.

(I could put a whole load more animated gif stuff in here like this and this and this and this. But I won’t. Except to say: animated gifs are the first artform of the internet, and they are in some way the future.)

→ German Tornado fighter with splinter camouflage.

→ Low resolution Lamborghini Countach, by United Nude

→ Lo Res Shoe, by United Nude

→ Fabricate Yourself, Karl D.D. Lewis

→ Telehouse West, by YRM Architects

The rough, pixelated, low-resolution edges of the screen are becoming in the world.

→ Robert Hodgin’s Kinect Fatsuit

→ NYC Street Art, photographed by Benjamin Norman

→ Minecraft

→ Embryo Firearms by Cornelia Parker

→→→→→→→→→→ And so on and so forth.

UPDATE: continuing the exploration at new-aesthetic.tumblr.com – submissions welcome.

(Some of these things might have appeared here, or nearby, before. They are not necessarily new new, but I want to put them together.)

For so long we’ve stared up at space in wonder, but with cheap satellite imagery and cameras on kites and RC helicopters, we’re looking at the ground with new eyes, to see structures and infrastructures:

→ Guardian gallery of agricultural landscapes from space.

→ Updates on Bin Laden’s Death, New York Times

→ Tracking iPhone locations with iPhoneTracker, from Ben on Flickr

The map fragments, visible at different resolutions, accepting of differing hierarchies of objects.

→ Tracking iPhone locations (Ongoing personal project)

→ Landscape Permutation 2 (2010), David Semeniuk

Views of the landscape are superimposed on one another. Time itself dilates.

→ Three screens (for London 2010)

→ FER IN 1970 & 2010, Buenos Aires, Back to the Future Series, Irina Werning

→ Luminant Point Arrays, by Stephan Tillmans

Representations of people and of technology begin to break down, to come apart not at the seams, but at the pixels.

→ Diptych 1 on Flickr (ongoing personal project)

→ CV Dazzle by Adam Harvey

→ Megabytes of Spring, Reed+Rader for vmagazine.com.

(I could put a whole load more animated gif stuff in here like this and this and this and this. But I won’t. Except to say: animated gifs are the first artform of the internet, and they are in some way the future.)

→ German Tornado fighter with splinter camouflage.

→ Low resolution Lamborghini Countach, by United Nude

→ Lo Res Shoe, by United Nude

→ Fabricate Yourself, Karl D.D. Lewis

→ Telehouse West, by YRM Architects

The rough, pixelated, low-resolution edges of the screen are becoming in the world.

→ Robert Hodgin’s Kinect Fatsuit

→ NYC Street Art, photographed by Benjamin Norman

→ Minecraft

→ Embryo Firearms by Cornelia Parker

→→→→→→→→→→ And so on and so forth.

UPDATE: continuing the exploration at new-aesthetic.tumblr.com – submissions welcome.

#sxaesthetic

March 15, 2012

Report from Austin, Texas, on the New Aesthetic panel at SXSW.

At SXSW this year, I asked four people to comment on the New Aesthetic, which if you don’t know is an investigation / project / tumblr looking at technologically-enabled novelty in the world.

(Previously: the original blog post, the main tumblr, my talk at Web Directions South.)

I opened the panel by talking about the origins of NA, in a frustration at retro-ness (the belief that authenticity can only be located in the past)—best encapsulated by Russell’s post here:

One of the core themes of the New Aesthetic has been our collaboration with technology, whether that’s bots, digital cameras or satellites (and whether that collaboration is conscious or unconscious), and a useful visual shorthand for that collaboration has been glitchy and pixelated imagery, a way of seeing that seems to reveal a blurring between “the real” and “the digital”, the physical and the virtual, the human and the machine. It should also be clear that this ‘look’ is a metaphor for understanding and communicating the experience of a world in which the New Aesthetic is increasingly pervasive.

What has been brilliant about the New Aesthetic for me, personally, is that it has produced work, it has made me see and think about the world in a strange way, out of which thinking strange things have fallen, like Rorschmap and Robot Flaneur and Balloon Drones and Shadows, of which more anon.

But what has also been brilliant is that other people have pitched in. I first realised that NA was “a thing” not in that first blog post (I would have given it a better name) but when people started responding and writing about it. They started coming to me, bringing things, and saying “is this New Aesthetic?” or even “I think this is New Aesthetic” and I’d go yes, possibly, or better, why do you think that?

Names have power (I showed a slide of Aleister Crowley at this point; hell, I’ll show it again—).

—giving something a name gives you power over it, but it also gives other people power too. Other people can pick up your tool and use it. (Sidenote, which we’ll return to: I’ve always loved this aspect of language. It’s at the core of the invisible book club, and the best example of it I’ve experienced lately is China Miéville’s “The City & The City” which yes I am still banging on about because it gives you new words—breeching, cross-hatching—for things you know but can’t describe and which you can use as keys to open the world in all its Sapir-Whorfian glory).

Anyway, the point about the brilliance of NA as a shareable concept is that other people respond, and I wanted to show that at SXSW by inviting four people—friends old and new—to respond as they saw fit, which might be any way at all. And they did, and you should read what they had to say (follow the links to their sites):

I came back on at the end to tell a few stories from the New Aesthetic. It was somewhat incoherent, in the way that talks are allowed to be but essays less so, but I shall try to lay it out.

I went to CERN, and one of the many great things about it is that people are doing things there in order to understand what they are doing, and it’s this vast iterative process with no definite outcome, but we do it because, perhaps, this is what we do when we encounter new things; we cannot do otherwise. We must stare at them ever longer and harder to understand what they mean.

Like this building and this photograph. The first is Telehouse’s new datacenter in East London which I have spoken about many times : why is it pixelated? Is it an attempt to render the network, the digital, visible? What form does the architecture of the network take, and what is the significance of the network’s irruption into physical space? (See also.)

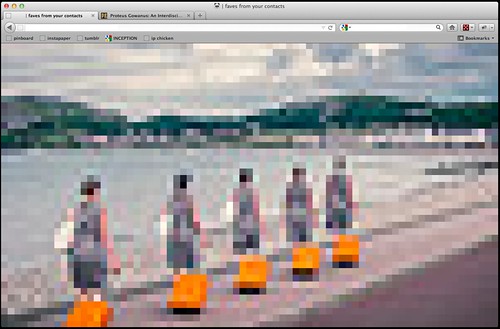

What is the extraordinary interweaving of events that must occur for this image to exist? (It is the Free Bradley Manning section of San Francisco Pride). How many networks have been traversed by ideas and images and people for this thing to happen and be seen? And what Julian Assange said [PDF]: “We must think beyond those who have gone before us, and discover technological changes that embolden us with ways to act in which our forebears could not.” If we have not found what we are looking for yet, what we are looking for must be found in the new.

And what of the render ghosts, those friends who live in our unbuilt spaces, the first harbingers of our collective future? How do we understand and befriend them, so that we may shape the future not as passive actors but as collaborators? (I don’t have much truck with the “don’t complain, build” / “make stuff or shut up” school, but I do believe in informed consent.)

Because a line has been crossed, technology/software/code is in and of the world and there’s no getting out of it. Some architects can look at a building and tell you which version of autodesk was used to create it. The world is defined by our visualisations of it. (Someone who makes such things told me: what they put in, even as place-holders, always ends up getting built. Lorem Ipsum architecture.)

People are writing stories about having sex with robots on the internet—turning all of literature and technology into creativity and amusement while simultaneously undermining all previous notions of authorial authority and intellectual property. (I was talking about slashfic and possibly starpunk too.)

People are “acting” in ways we may or may not understand, which may or may not have an effect in the real world, whether it’s signing petitions, organising riots (on BBM), clicking, ‘liking’ KONY, whatever, the correct (maybe) response is not to have an opinion (default internet response, still) or a moral position, but to live inside the thing as it unfolds.

I think at this point I might have quoted Kafka and then gone on a rant about how brilliant Tumblr is:

I said that we need to invent new words for everything, preferably/not really Long German ones, because we are experiencing genuinely new things, and we should not shy away from that fact. Yes, everything has always been new and different and everything has always been the same, but we can perform an end-run around this endless back-and-forth between contemporary boosterism and conservative ever-wasness by getting excited about the fact that new ways of seeing (/thinking) produce if not a new world then new sensations which are the medium by which we appreciate a new world (and for that tug at your heart, that drop in your stomach, when you see a distant place through the internet and a number of devices (including your friends drinking in a distant city in real-time on Twitter) and wish you were there I coin the term Strasseblickfernweh, or Street View wanderlust.)

I wrote this rant a while back on Flickr, about, essentially, the uneven distribution of exciting futures (there was something in the air last summer / there is always something in the air if you’re facing the right way)…

And Tom said:

Also, what Rilke said:

My point is, all our metaphors are broken. The network is not a space (notional, cyber or otherwise) and it’s not time (while it is embedded in it at an odd angle) it is some other kind of dimension entirely.

BUT meaning is emergent in the network, it is the apophatic silence at the heart of everything, that-which-can-be-pointed-to. And that is what the New Aesthetic, in part, is an attempt to do, maybe, possibly, contingently, to point at these things and go but what does it mean?

There’s a round-up of tweets from the session here (thanks to Paul), as well as a bunch from Bruce Sterling’s SXSW closing keynote (thanks to Chris), when he declared the NA to be at least one kind of future. He also wrote it up for Wired.

Thanks very much to Joanne, Ben, Aaron and Russell for agreeing to and indeed taking part in this ongoing discussion (do read their blog posts), also to Chris and George for moral support, and to everyone who came. All will continue, no doubt, here and at the NA.

At SXSW this year, I asked four people to comment on the New Aesthetic, which if you don’t know is an investigation / project / tumblr looking at technologically-enabled novelty in the world.

(Previously: the original blog post, the main tumblr, my talk at Web Directions South.)

I opened the panel by talking about the origins of NA, in a frustration at retro-ness (the belief that authenticity can only be located in the past)—best encapsulated by Russell’s post here:

Every hep shop seems to be full of tweeds and leather and carefully authentic bits of restrained artisinal fashion. I think most of Shoreditch would be wondering around in a leather apron if it could. With pipe and beard and rickets. Every new coffee shop and organic foodery seems to be the same. Wood, brushed metal, bits of knackered toys on shelves. And blackboards. Everywhere there’s blackboards.—as well as a real sense that there were new and extraordinary things and experiences in the world, like the ability to see through satellites, which we should wonder at and explore, but instead reduce to the mundane, like GPS driving directions…

One of the core themes of the New Aesthetic has been our collaboration with technology, whether that’s bots, digital cameras or satellites (and whether that collaboration is conscious or unconscious), and a useful visual shorthand for that collaboration has been glitchy and pixelated imagery, a way of seeing that seems to reveal a blurring between “the real” and “the digital”, the physical and the virtual, the human and the machine. It should also be clear that this ‘look’ is a metaphor for understanding and communicating the experience of a world in which the New Aesthetic is increasingly pervasive.

What has been brilliant about the New Aesthetic for me, personally, is that it has produced work, it has made me see and think about the world in a strange way, out of which thinking strange things have fallen, like Rorschmap and Robot Flaneur and Balloon Drones and Shadows, of which more anon.

But what has also been brilliant is that other people have pitched in. I first realised that NA was “a thing” not in that first blog post (I would have given it a better name) but when people started responding and writing about it. They started coming to me, bringing things, and saying “is this New Aesthetic?” or even “I think this is New Aesthetic” and I’d go yes, possibly, or better, why do you think that?

Names have power (I showed a slide of Aleister Crowley at this point; hell, I’ll show it again—).

—giving something a name gives you power over it, but it also gives other people power too. Other people can pick up your tool and use it. (Sidenote, which we’ll return to: I’ve always loved this aspect of language. It’s at the core of the invisible book club, and the best example of it I’ve experienced lately is China Miéville’s “The City & The City” which yes I am still banging on about because it gives you new words—breeching, cross-hatching—for things you know but can’t describe and which you can use as keys to open the world in all its Sapir-Whorfian glory).

Anyway, the point about the brilliance of NA as a shareable concept is that other people respond, and I wanted to show that at SXSW by inviting four people—friends old and new—to respond as they saw fit, which might be any way at all. And they did, and you should read what they had to say (follow the links to their sites):

- Joanne McNeil, editor of Rhizome, spoke about the history of new aesthetics, on new perspectives, technologies and art.

- Ben Terrett, designer, on the New Aesthetic in commercial visual culture.

- Aaron Straup Cope, artist and developer, on drones, data and human geography.

- Russell Davies, reckoner of this parish, on the New Aesthetic and writing.

I came back on at the end to tell a few stories from the New Aesthetic. It was somewhat incoherent, in the way that talks are allowed to be but essays less so, but I shall try to lay it out.

I went to CERN, and one of the many great things about it is that people are doing things there in order to understand what they are doing, and it’s this vast iterative process with no definite outcome, but we do it because, perhaps, this is what we do when we encounter new things; we cannot do otherwise. We must stare at them ever longer and harder to understand what they mean.

Like this building and this photograph. The first is Telehouse’s new datacenter in East London which I have spoken about many times : why is it pixelated? Is it an attempt to render the network, the digital, visible? What form does the architecture of the network take, and what is the significance of the network’s irruption into physical space? (See also.)

What is the extraordinary interweaving of events that must occur for this image to exist? (It is the Free Bradley Manning section of San Francisco Pride). How many networks have been traversed by ideas and images and people for this thing to happen and be seen? And what Julian Assange said [PDF]: “We must think beyond those who have gone before us, and discover technological changes that embolden us with ways to act in which our forebears could not.” If we have not found what we are looking for yet, what we are looking for must be found in the new.

And what of the render ghosts, those friends who live in our unbuilt spaces, the first harbingers of our collective future? How do we understand and befriend them, so that we may shape the future not as passive actors but as collaborators? (I don’t have much truck with the “don’t complain, build” / “make stuff or shut up” school, but I do believe in informed consent.)

Because a line has been crossed, technology/software/code is in and of the world and there’s no getting out of it. Some architects can look at a building and tell you which version of autodesk was used to create it. The world is defined by our visualisations of it. (Someone who makes such things told me: what they put in, even as place-holders, always ends up getting built. Lorem Ipsum architecture.)

People are writing stories about having sex with robots on the internet—turning all of literature and technology into creativity and amusement while simultaneously undermining all previous notions of authorial authority and intellectual property. (I was talking about slashfic and possibly starpunk too.)

People are “acting” in ways we may or may not understand, which may or may not have an effect in the real world, whether it’s signing petitions, organising riots (on BBM), clicking, ‘liking’ KONY, whatever, the correct (maybe) response is not to have an opinion (default internet response, still) or a moral position, but to live inside the thing as it unfolds.

I think at this point I might have quoted Kafka and then gone on a rant about how brilliant Tumblr is:

You do not need to leave your room. Remain sitting at your table and listen. Do not even listen, simply wait, be quiet still and solitary. The world will freely offer itself to you to be unmasked, it has no choice, it will roll in ecstasy at your feet.

I said that we need to invent new words for everything, preferably/not really Long German ones, because we are experiencing genuinely new things, and we should not shy away from that fact. Yes, everything has always been new and different and everything has always been the same, but we can perform an end-run around this endless back-and-forth between contemporary boosterism and conservative ever-wasness by getting excited about the fact that new ways of seeing (/thinking) produce if not a new world then new sensations which are the medium by which we appreciate a new world (and for that tug at your heart, that drop in your stomach, when you see a distant place through the internet and a number of devices (including your friends drinking in a distant city in real-time on Twitter) and wish you were there I coin the term Strasseblickfernweh, or Street View wanderlust.)

I wrote this rant a while back on Flickr, about, essentially, the uneven distribution of exciting futures (there was something in the air last summer / there is always something in the air if you’re facing the right way)…

And Tom said:

It’s 2011, and I have no idea what anything is or does anymore.At CERN, there was a video where a particle physicist was asked “What if you don’t find the Higgs Boson? What if you’re wrong about this?” and he thought that would be brilliant, because then they’d know a whole area they could block out and go OK, not this, but how about this?

Also, what Rilke said:

Perhaps all the dragons in our lives are princesses who are only waiting to see us act, just once, with beauty and courage. Perhaps everything that frightens us is, in its deepest essence, something helpless that wants our love.Which must be true because Rilke said it (what would you bring down from the mountain?).

My point is, all our metaphors are broken. The network is not a space (notional, cyber or otherwise) and it’s not time (while it is embedded in it at an odd angle) it is some other kind of dimension entirely.

BUT meaning is emergent in the network, it is the apophatic silence at the heart of everything, that-which-can-be-pointed-to. And that is what the New Aesthetic, in part, is an attempt to do, maybe, possibly, contingently, to point at these things and go but what does it mean?

There’s a round-up of tweets from the session here (thanks to Paul), as well as a bunch from Bruce Sterling’s SXSW closing keynote (thanks to Chris), when he declared the NA to be at least one kind of future. He also wrote it up for Wired.

Thanks very much to Joanne, Ben, Aaron and Russell for agreeing to and indeed taking part in this ongoing discussion (do read their blog posts), also to Chris and George for moral support, and to everyone who came. All will continue, no doubt, here and at the NA.

Report from the New Aesthetic: The Movement Rolls On, Inward

The New Aesthetic took off soon after, thanks to a response essay to that panel by respected tech writer Bruce Sterling, hailing it as the new avant-garde. His case for the New Aesthetic as a legit movement was helped by the fact that Bridle’s fellow panelists included a bevy of art-tech public intellectuals: Rhizome Senior Editor Joanne McNeil, Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum Senior Engineer Aaron Straup Cope, Wired UK Contributing Editor Russell Davies, and the UK Government Digital Service’s Head of Design Ben Terrett.

Sterling’s essay provoked months of more response essays, and responses to those responses. On average, the New Aesthetic seems to get more of a rise from technologists, less with artists, and least with art writers. Critics mostly agree that something’s happening, but feel that the New Aesthetic doesn’t ask the hard questions (Gannis, Chayka, Zigelbaum and Marcelo Coelho). It needs to get weirder; it needs to move past shared images; it needs to go native; it needs focus. Art writers in particular knocked its remarkably short memory. The arts community seemed nonplussed by the idea of creating a new worldview based on a collection of images. As tech-minded artists like Jamie Zigelbaum and Marcelo Coelho and Carla Gannis have pointed out, art already does that.

After a few months’ lull in the dialogue, Rhizome’s Joanne McNeil arranged another panel at the New Museum called “Stories from the New Aesthetic”. Its makeup showed how much the ongoing public discussion has impacted the project: all three speakers were on the previous talk, at SXSW. Tickets were sold out for a largely student-aged audience. “Artists are starting to make things that look like the Internet,” I heard one someone explain behind me, thus providing my only primer (the handful of people I met afterwards hadn’t heard much more than that). Like Bridle’s essay earlier this year, panelists wandered through the garden of the Internet, cherry-picking what fit the theory; the discussion felt similar to the tailoring of a Tumblr or Pinterest experience. As such, they all looked and sounded the same. Artists were rarely mentioned, but there were a lot of Streetview screenshots.

Aaron Straup Cope (whose full talk you can read here) loosely structured his presentation around the idea that programming reveals something about our own motives. Self-driving cars would have to be preventatively-programmed, for instance, while Siri leaves room for the illusion of new interactions. Looking through technology opens up our view of the world, he argued, pointing to how Instagram filters compel people to post more photos.

But then he extended the idea that we’re just barely keeping on top of technological advancement with the implication that robots can actually see:

But Cope didn’t have any proof of artificial intelligence, beyond the existence of drones— apparently, self-evident because they appear to drive themselves. As new media documentarian Jonathan Minard, among others, has pointed out, the New Aesthetic’s intrigue hinges on imagining that you’re seeing these images through the sentient eyes and mind of a robot, as though the webcam is looking back. When recalibrated as the human images which these are, we just end up with far more shitty photos and less privacy.There is a larger question of whether our willingness to allow the robots to act of their own accord on [looking for patterns] constitutes de facto seeing but, by and large, we continue to actively side-step that question.

Joanne McNeil (full talk here) described the psychic space created by machines, as revealed in things she did on the Internet, like posting a photo of a jellyfish as a location on Instagram, or fantasy images that are a result of computer programs, like a realistic rendering of a seemingly infinite bookshelf. McNeil mentioned projects like Dora Moutot’s “Webcam Tears” and Clement Valla’s collection of Google Earth glitches (also part of the current show “Collect the WWWorld” at 319 Scholes), but they were treated as vessels to look at Internet trends, rather than intentional creative acts. Like Cope, she flipped between slides of what the camera sees (Google Street View interiors) and dead-on images of the lens: again, literally assigning the camera a personality.

McNeil held no reservations about her motive to promote the project, concluding: “It’s not radical to point out that the digital and the physical co-exist and that they’re layered upon each other, but it is still unusual, and it’s something that we’re experiencing right now….and it’s why I think the New Aesthetic project is quite valuable.” But if we’re going to declare Bridle’s project as significant as the change it documents, then the same could be said of any number of documentary projects—people who are collecting Occupy Wall Street photos, for one. That’s wishful thinking—people rarely get what they deserve in the art world—but you can expect people to deliver. McNeil’s in the business of promoting artists.

New Aesthetic founder James Bridle then seized the stage: wildly gesticulating, he poured forth a double-time of storytelling and slides, interjecting things like “and yet, and yet, and yet!” I get now why Bruce Sterling described the New Aesthetic as being in its “evangelical, podium-pounding phase.”

It’s important to note that, since the SXSW panel, Bridle has been making less of a logical observation than a visceral appeal. He thinks of a Kafka quote in terms of Tumblr:

You do not need to leave your room. Remain sitting at your table and listen. Do not even listen, simply wait, be quiet still and solitary. The world will freely offer itself to you to be unmasked, it has no choice, it will roll in ecstasy at your feet.You can experience an elite revolution, in other words, without doing anything. The New Aesthetic promises a Whitman-esque romp into the endless scroll, over the pop fetishization of the pre-computer age.

That zeal came through in the sermon. He started out by lecturing us on what he sees as a widespread reluctance to embrace the inevitable. “Nobody talked about the smell of the book until people started worrying about e-books,” he said.

He told us that, when it comes to books, what people really care about is: the ability to discuss them, to keep your place, a sense of ownership, and the souvenir of your experience with them. E-books, according to Bridle, “haven’t quite figured that out yet.”…even though those things were completely irrelevant, but we had nowhere else to put our fears about what actually might happen…that we identified the cultural importance of literature so closely with a physical object that we could only tie it to its physicality.

But herein lies the problem with the entire panel: no matter how robotic we’re striving to be, market research doesn’t substitute for human experience. Maybe it doesn’t make as much sense to own a physical copy of Fifty Shades of Grey, but the act of reading an e-book is more than gleaning necessary information from row after row of code. Like any object, the book can also be a gift, an heirloom, an antique, a physical record of someone’s life. All that physicality is inconveniently sentimental.

E-books were just one example of how we’d better get with the program before technology eclipses us. Here, Bridle told us about code/spaces: a name professors and co-authors Rob Kitchin and Martin Dodge gave to physical locations like airport waiting rooms or the Amazon warehouse that are organized by software, without which, they become totally useless. But should the power shut off as it did a few weeks ago, I still managed to find the temporary subway shuttle without my phone; I asked someone.

Then another slideshow of New Aesthetic-y stuff. Bridle mentioned Clement Valla, who he’s a “huge fan of,” possibly because Valla’s collecting map glitches, which Bridle half-jokingly described as “one of the largest New Aesthetic artworks ever.” Ha, ha. He’s recently filed Sandy images under that moniker, as well. “It doesn’t matter that most of these things are banal. That’s kind of the point,” he told us. Computer systems are so ingrained in our way of seeing the work that the point is to examine how we’re looking, not the actual products of looking. It was the only statement he made that night that showed signs of even searching for revelation, let alone finding one.

But even that is more of an observation than a takeaway. As artist and digital media professor Carla Gannis wrote of the New Aesthetic back in May, “A movement cannot merely catalogue what currently exists, it is defined by the future(s) it envisions.”

That future materialized in one of Bridle’s more memorable quotes: “Opinions are non-contemporary.” That’s a funny idea to table amongst a panel of speakers who all happened to share one, very strong opinion. Nobody’s changing their mind about what they like; Bridle’s vision seems to diminish empathy more than anything else. Luckily, we were all spared the Q&A, as rows of the audience stood up and walked out as soon as the lights went up.

Seven posts about the future

Late March, 2011, and a lot has been building up. Too much yammering, not enough hammering. So, in an attempt to clear the decks, a braindump.

These seven posts are mostly culled from the last year of notebooks, of the commonplace book. They may be conceptually linked, but only in my head. They may employ strategic and/or naive misunderstandings. They may be confused.

Still: we write.

These seven posts are mostly culled from the last year of notebooks, of the commonplace book. They may be conceptually linked, but only in my head. They may employ strategic and/or naive misunderstandings. They may be confused.

Still: we write.

- Hauntological Futures

- Starpunk

- Stop Lying About What You Do

- An Elixir of Reminding

- The House of Wisdom

- #wikileakspaper

- The Author of Everything

Hauntological Futures

March 20, 2011

This post is the first of seven posts about the future. Caveat lector.

Both are also easily misunderstood, oversimplified, and recuperated. Before that happens, we might as well attempt to wring something useful out of it. It’s been knocking around the music/philosophy blogs for a while, so it’s probably time to think about it in the literature space.

Hauntology in one sense is a term for a certain strand of music, characterised by the sampling or emulation of old times and old effects: childrens’ TV themes and the BBC radiophonic workshop, Oliver Postgate and 90s rave. That glib recitation is another waymark on the road to recuperation, but. Read more, and more widely.

Hauntology is also a network effect engendered by the increasing apparent* flattening of history and time. The network, fragmented and unevenly distributed, induces a growing sense that alternative worlds are very close indeed.

( * The internet only appears to be flat, as we perceive it in two dimensions. In fact, the knowledge it embodies, because it is tied to and instantiated in time, is ever receding from us, darkening and thickening and coming apart, becoming harder to reach and harder to find. The past is intractable but loosened, suffering our gaze upon it and our endless reinterpretations of it.)

As such, it is amenable to the same critical apparatus as Network Realism: indeed, it may be a part of the same thing.

While I understand the distinction between nostalgia and hauntology, I am unconvinced by their separation in the application of the latter to music. The two most frequently cited sonic hauntologists are Burial and Ghost Box records, and while I’m a huge fan of both, I also see them as being steeped in nostalgia.

I am so bored of nostalgia. Of letterpress and braces and elaborate facial hair. I appreciate these things, but I think there’s something wrong with a culture that fetishises them to the extent that we currently do.

As if authenticity is only to be found in the past. I think we are frightened and I think we are distrustful and we are worried that things are slipping away. (This is something I am going to address separately.)

What would a hauntological literature look like? I’m not sure, and that makes me suspicious. The two things that come to mind are Borges (surprise!) and starpunk, which I’m also going to write about separately.

Much hauntology fails because it continues to assert a backwards/forwards model of time, a resurrection of an imagined past which is still too drenched in pure nostalgia to serve any revolutionary purpose.

Hauntology feels like a symptom of future shock, a reaction. Caisson disease: a form of the bends brought on by too rapid changes of pressure when moving between the different levels (pressurised chambers) of the caissons used in building bridges. A symptom of the unevenly-distributed future, the isobars of our ever-shifting and expanding culture.

Another test of hauntology is how it stands up to other reactions to present conditions. Bill Drummond’s The17 project is an attempt to reimagine music, its genesis in a rejection of the past. (The book.)

He imposes a restriction: “only listen to music written, recorded or released in the previous twelve months by composers, soloists or ensembles who have never released music in any format at any time previous to the last twelve months.”

But, Bill is disappointed: “everything I bought sounded like something I had heard 10, 20, 30 years before.”

Out of this, and a number of other realisations, comes The17. This is the opposite of hauntology: to demand the radically new. Hauntology reinvigorates, reanimates the past—allegedly—turning the old musics to new purpose, much as Borge’s Pierre Menard does to the Quixote.

I think my problem with hauntology is that it deals with the problem of the future by going back to the past. And that is fine: but it will not save us.

“Hauntology is a coming to terms with the permanence of our (dis)possession, the inevitability of dyschronia.Hauntology, already old, is about six months away from becoming the title of a column in a Sunday supplement magazine; of going the way of psychogeography. The two have much in common: one concerns expeditions in space, the other in time. (“Kant thought that space was the form of our outer experience, and time the form of our inner experience”—Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia.)

“I repeat, I re-cite: hauntology is the closest thing we have to a movement, a zeitgeist, at the moment (and one of the uncanniest aspects of it is the fact that there seem to be very few lines of explicit influence among the artists involved).”

—Mark Fisher (k-punk)

Both are also easily misunderstood, oversimplified, and recuperated. Before that happens, we might as well attempt to wring something useful out of it. It’s been knocking around the music/philosophy blogs for a while, so it’s probably time to think about it in the literature space.

Hauntology in one sense is a term for a certain strand of music, characterised by the sampling or emulation of old times and old effects: childrens’ TV themes and the BBC radiophonic workshop, Oliver Postgate and 90s rave. That glib recitation is another waymark on the road to recuperation, but. Read more, and more widely.

Hauntology is also a network effect engendered by the increasing apparent* flattening of history and time. The network, fragmented and unevenly distributed, induces a growing sense that alternative worlds are very close indeed.

( * The internet only appears to be flat, as we perceive it in two dimensions. In fact, the knowledge it embodies, because it is tied to and instantiated in time, is ever receding from us, darkening and thickening and coming apart, becoming harder to reach and harder to find. The past is intractable but loosened, suffering our gaze upon it and our endless reinterpretations of it.)

As such, it is amenable to the same critical apparatus as Network Realism: indeed, it may be a part of the same thing.

“Ghost Box and, in particular, Belbury Poly are not inspired by the hackneyed futurism that pulsed through earlier electronic music. Their interest lies in lost worlds and an England imagined as Arcadia, in tracks such as Pan’s Garden, which sounds, thrillingly, like morris-dance music made with synths.”(“Hackneyed futurism” is key here: the future we were promised, of living in space, of jetpacks and pellet foods, is simply not going to happen. And while we reject the macho dark survivalist future of envirotechnological collapse, we also must give up the NASA-Concorde extopia we have been pining for forever: these are the futures of an extinguished past, a worldline that didn’t work out, a dead end.)

- The Times

While I understand the distinction between nostalgia and hauntology, I am unconvinced by their separation in the application of the latter to music. The two most frequently cited sonic hauntologists are Burial and Ghost Box records, and while I’m a huge fan of both, I also see them as being steeped in nostalgia.

I am so bored of nostalgia. Of letterpress and braces and elaborate facial hair. I appreciate these things, but I think there’s something wrong with a culture that fetishises them to the extent that we currently do.

As if authenticity is only to be found in the past. I think we are frightened and I think we are distrustful and we are worried that things are slipping away. (This is something I am going to address separately.)

What would a hauntological literature look like? I’m not sure, and that makes me suspicious. The two things that come to mind are Borges (surprise!) and starpunk, which I’m also going to write about separately.

Much hauntology fails because it continues to assert a backwards/forwards model of time, a resurrection of an imagined past which is still too drenched in pure nostalgia to serve any revolutionary purpose.

Hauntology feels like a symptom of future shock, a reaction. Caisson disease: a form of the bends brought on by too rapid changes of pressure when moving between the different levels (pressurised chambers) of the caissons used in building bridges. A symptom of the unevenly-distributed future, the isobars of our ever-shifting and expanding culture.

Another test of hauntology is how it stands up to other reactions to present conditions. Bill Drummond’s The17 project is an attempt to reimagine music, its genesis in a rejection of the past. (The book.)

He imposes a restriction: “only listen to music written, recorded or released in the previous twelve months by composers, soloists or ensembles who have never released music in any format at any time previous to the last twelve months.”

But, Bill is disappointed: “everything I bought sounded like something I had heard 10, 20, 30 years before.”

Out of this, and a number of other realisations, comes The17. This is the opposite of hauntology: to demand the radically new. Hauntology reinvigorates, reanimates the past—allegedly—turning the old musics to new purpose, much as Borge’s Pierre Menard does to the Quixote.

I think my problem with hauntology is that it deals with the problem of the future by going back to the past. And that is fine: but it will not save us.

Starpunk

March 21, 2011

This post is the second of seven posts about the future. Caveat lector.

Steampunk, while now well-distributed and originally offshore, feels quite British. A fetishisation of the difficult, the complex, the grimy, the high-friction and the physical. Engineering-fic. But too often it’s also a default position for a certain kind of literature, like London’s ‘gaslight mode’, that pea-souper, Jack The Ripper, Neverwhere Victoriana that sometimes feels like it’s deadening capital fictions. There must be other ways to mess with histories.

In a recent interview Michael Moorcock had this to say:

It’s a call for a steampunk that explores all the conditions of its history: of the mill, and of the workhouse. It’s the same impulse that, when a friend throws a 1920s party, makes me want to turn up as a polio victim.

So steampunk—hell, *punk—is the retrofitting of today’s potentialities onto the technologies of an arbitrary point in the past. By doing so, those potentialities are made visible: like the distributed communication / packet switching encoded as pillars in the landscape in Keith Roberts’ proto-steampunk novel Pavane.

(That opening line about fetishising the difficult is actually a half-remembered quote from somewhere about the Britishness of Newspaper Club: a retrofit of potentialities onto older technologies if ever there was one.)

So, we can retrofit onto other periods too. Like Dieselpunk, “a subculture and a genre of art blending the aesthetics of the 1920s through the early 1950s with today”, whose self-description declares itself to be entirely aesthetic, prefiguring its devolution into bobby-socks, greaseballs and hotrods rather than anything political.

What about cavepunk, a potential genre that must exist somewhere between Modern Primitives and the Flintstones’ Family Saloon? I’m seeing a lot of fire, and a political focus on anarcho-primitivism and “rewilding”.

When I asked Russell a while back for alternatives to steampunk, he suggested 80s-punk, all massive walkmans and Nike Air Jordans. Back To The Future 2. Technology without the network. Fashionpunk (no).

Can *punk belong to the future, or is it predicated on past knowns? Cyberpunk did and wasn’t: it defined a territory by parodying it (Gibson was always a Beat writer). Likewise the developing-world futurism promised by AfroCyberPunk, which I keep linking to in an effort to will it into being (/being better). Gurgaonpunk. Paulistapunk.

I want to read a near-future enviropunk, where pandas are fed into woodchippers to give us the escape velocity to move beyond enviroconservatism.

Not Salvagepunk, which is merely a hauntological critique of *punk. Salvagepunk is total Dark Mountain, even while it rightly eviscerates hauntology’s endless wibbling about in the tickets of history as “pseudo-Leftist” in the worst sense: factional, morose, yearning for some never-never Golden Age of the past.

*punk is not the same as speculative fiction or alternative history. It’s more focused on technology, and the social implications of technology, than pure spec.fic or alt.hist. That’s what ties it ideally to Science Fiction, and why Sci Fi writers have started to rail against steampunk’s perceived decadence.

But it is definitely tied to time, which suggests there is a path to be made to Network Realism. Even if *punk can be considered anti-realist by definition, we can borrow some of its tools. Are all *punks subsets of timepunk? Or do they merely appear so because of a technological focus that so clearly situates and timestamps them?

(And I’m interested, I realise, because I want Network Realism for precisely the same reasons that Moorcock and Stross decry the aesthetisisation of steampunk: because the aesthetisisation of anything is an abdication of its politics, because the aesthetisisation of politics is fascism, and fascism is the opposite of imagination. We have too many dead literatures.)

If *punk doesn’t have to be about technology, what else can it be about?

Can we locate *punk in forbidden modes of writing, like slashfic, a proto-pornpunk, retrofitting different desires onto existing characters and situations? (Yes, we can.)

Thus, we locate *punk in the quietly radical queer writings of JR Ackerley and Jocelyn Brooke in the years before Wolfenden. These works inhabit a space of imminent possibility imagined by the writers as a way of calling such spaces into being, collapsing the quantum society of the time, full of hypocrises and hidden allowances. If designers are concerned with the recently possible, writers should be concerned with the imminent.

Essentially, *punk is a hollowing out of conceptual spaces based on only slightly varied worldlines. It may be subsumed by aesthetics, as is the problem with most bad steampunk (“stick some brass cogs on it”), but it may also uncover previously hidden possibilities.

*

Update, because there are going to be more:

Steampunk, while now well-distributed and originally offshore, feels quite British. A fetishisation of the difficult, the complex, the grimy, the high-friction and the physical. Engineering-fic. But too often it’s also a default position for a certain kind of literature, like London’s ‘gaslight mode’, that pea-souper, Jack The Ripper, Neverwhere Victoriana that sometimes feels like it’s deadening capital fictions. There must be other ways to mess with histories.

In a recent interview Michael Moorcock had this to say:

MM: In [1971 novel] The Warlord of the Air, for instance, I invented this specific form to do a specific job. And then 10 years later, 20 years later, I’m suddenly dragged into the steampunk movement, as a steampunk writer, which I wasn’t. And again, it’s disappointing to me, because very little steampunk that I’ve read actually does what I was trying to do with Warlord of the Air, which was, I was basically looking at, if you like, a Fabian view of Colonialism. It was an idea of Benign Colonialism, which I didn’t believe in. And I was trying to explore that.Charlie Stross had a crack at the same problem: the depoliticisation, or absence of politics at all, in the genre, proposing an alternative steampunk that takes “the taproot history of the period seriously”:

Yeah. Whereas a lot of the steampunk doesn’t have that intellectual content, it just uses the period imagery.

MM: Yes, that’s right, and they think, “oh great, big airships! Wow!” You’re a bit suspicious of people who like too many big airships. You think, maybe you should be writing porn, you know!

Forget wealthy aristocrats sipping tea in sophisticated London parlours; forget airship smugglers in the weird wild west. A revisionist mundane SF steampunk epic — mundane SF is the socialist realist movement within our tired post-revolutionary genre — would reflect the travails of the colonial peasants forced to labour under the guns of the white Europeans’ Zeppelins, in a tropical paradise where severed human hands are currency and even suicide doesn’t bring release from bondage.Stross’ argument is that second artist syndrome has stripped the genre of its politics and its scientific understanding, leaving it nothing but aesthetics (“nothing more than what happens when goths discover brown”).

It’s a call for a steampunk that explores all the conditions of its history: of the mill, and of the workhouse. It’s the same impulse that, when a friend throws a 1920s party, makes me want to turn up as a polio victim.

So steampunk—hell, *punk—is the retrofitting of today’s potentialities onto the technologies of an arbitrary point in the past. By doing so, those potentialities are made visible: like the distributed communication / packet switching encoded as pillars in the landscape in Keith Roberts’ proto-steampunk novel Pavane.

(That opening line about fetishising the difficult is actually a half-remembered quote from somewhere about the Britishness of Newspaper Club: a retrofit of potentialities onto older technologies if ever there was one.)

So, we can retrofit onto other periods too. Like Dieselpunk, “a subculture and a genre of art blending the aesthetics of the 1920s through the early 1950s with today”, whose self-description declares itself to be entirely aesthetic, prefiguring its devolution into bobby-socks, greaseballs and hotrods rather than anything political.

What about cavepunk, a potential genre that must exist somewhere between Modern Primitives and the Flintstones’ Family Saloon? I’m seeing a lot of fire, and a political focus on anarcho-primitivism and “rewilding”.

When I asked Russell a while back for alternatives to steampunk, he suggested 80s-punk, all massive walkmans and Nike Air Jordans. Back To The Future 2. Technology without the network. Fashionpunk (no).

Can *punk belong to the future, or is it predicated on past knowns? Cyberpunk did and wasn’t: it defined a territory by parodying it (Gibson was always a Beat writer). Likewise the developing-world futurism promised by AfroCyberPunk, which I keep linking to in an effort to will it into being (/being better). Gurgaonpunk. Paulistapunk.

I want to read a near-future enviropunk, where pandas are fed into woodchippers to give us the escape velocity to move beyond enviroconservatism.

Not Salvagepunk, which is merely a hauntological critique of *punk. Salvagepunk is total Dark Mountain, even while it rightly eviscerates hauntology’s endless wibbling about in the tickets of history as “pseudo-Leftist” in the worst sense: factional, morose, yearning for some never-never Golden Age of the past.

*punk is not the same as speculative fiction or alternative history. It’s more focused on technology, and the social implications of technology, than pure spec.fic or alt.hist. That’s what ties it ideally to Science Fiction, and why Sci Fi writers have started to rail against steampunk’s perceived decadence.

But it is definitely tied to time, which suggests there is a path to be made to Network Realism. Even if *punk can be considered anti-realist by definition, we can borrow some of its tools. Are all *punks subsets of timepunk? Or do they merely appear so because of a technological focus that so clearly situates and timestamps them?

(And I’m interested, I realise, because I want Network Realism for precisely the same reasons that Moorcock and Stross decry the aesthetisisation of steampunk: because the aesthetisisation of anything is an abdication of its politics, because the aesthetisisation of politics is fascism, and fascism is the opposite of imagination. We have too many dead literatures.)

If *punk doesn’t have to be about technology, what else can it be about?

Can we locate *punk in forbidden modes of writing, like slashfic, a proto-pornpunk, retrofitting different desires onto existing characters and situations? (Yes, we can.)

Thus, we locate *punk in the quietly radical queer writings of JR Ackerley and Jocelyn Brooke in the years before Wolfenden. These works inhabit a space of imminent possibility imagined by the writers as a way of calling such spaces into being, collapsing the quantum society of the time, full of hypocrises and hidden allowances. If designers are concerned with the recently possible, writers should be concerned with the imminent.

Essentially, *punk is a hollowing out of conceptual spaces based on only slightly varied worldlines. It may be subsumed by aesthetics, as is the problem with most bad steampunk (“stick some brass cogs on it”), but it may also uncover previously hidden possibilities.

*

Update, because there are going to be more:

- Farmpunk via Matt Jones / Warren Ellis

Stop Lying About What You Do

March 23, 2011

This post is the third of seven posts about the future. Caveat lector.

I think it was only during the second Lord of the Rings film, The Two Towers, that it hit me. Hang on: I remember this. I remember not liking this.

Like so many others, I was excited by the prospect of the LOTR films. I loved LOTR! I was one of those quite geeky but smart kids who revelled in that imaginary, epic world. I’d read the books several times. It wasn’t until the above moment that I realised I had made this up.

Somewhere between reading the books and reaching my twenties, I had convinced myself that I was the sort of person who liked LOTR, who had read it as a kid, and again as a teenager. Convinced myself utterly. It took the buttock-numbing horror of Sam and Frodo’s long march to remind me that I hated Tolkien almost as much as I hated CS Lewis, and I needed to get out now—and bin the expensive set of LOTR hardbacks I’d recently bought and never opened.

The same impulse can be seen in the endless lies we tell others about ourselves, half-believing them. As a vegetarian (uncaring, unsentimental), I get this from carnivores all the time, it’s oddly pervasive. “Oh, we don’t eat much meat at home.” “I could give up meat.” “I’m almost vegetarian.”

“I don’t watch much TV” is the other one, when you tell people you don’t have a TV. (I don’t have a TV. I watch a bit of TV on the internet. I lie about how much. I’m lying now.)

The most offensive one: “I’d much rather shop at a little local shop.” Bullshit. If you did, there would be no Tescos. But you campaign against it and you petition the council and when it opens you shop there anyway and the little shops die, and you justify it because it’s there now, but that is precisely when action should be taken.

This willful lying to oneself is everywhere; it is particularly evident in attitudes to the future.

Everyone in publishing: “Ebooks will never catch on.” And in the same breath: “but I love my Kindle. It’s so useful for reading manuscripts/reports/whatever.”

Shmuel, a Flickr user and copywriter, put together this excellent bingo card of lies publishers tell themselves, willfully or not. The Ur-comment is at bottom right: “Evidence that doesn’t fit my beliefs is wrong.” What is extraordinary is that this continues even when we ourselves are generating the evidence, when we are our own exceptions.

We prejudge endlessly. Because we have not experienced the emotions that new technologies trigger we assume that they will be less powerful than the emotions we already know. Just because we haven’t had these feelings yet. I love books. But I know that ereading will inspire a whole new range of responses to the written word and I want these too (I am trying to collect them).

I am not saying this is easy. Bill Drummond again:

I don’t read like I used to—although that’s not necessarily a bad thing. I rarely finish books. I’ve always had a habit of abandoning novels 50-100 pages before the end. I don’t know why, I’ve always done that. I think I’m doing it more and I don’t mind because I think my critical senses have improved and by eradicating book guilt I’ve reached a point where I am happy to cast things aside. I read 5, 10 books at once. I read them on paper and electronically as the mood takes me.

I read with continuous partial attention and I don’t care that I am frequently interrupting my own reading. I despise the discourse that says we are all shallow, that we are all flighty, distracted, not paying attention. I am paying attention, but I am paying attention to everything, and even if my knowledge is fragmented and hard to synthesise it is wider, and it plays in a vaster sphere, than any knowledge that has gone before.

I go through cycles of belief about the future of writing, of publishing, of the written word. But too much is broken to continue to pretend that the models we have become used to, the models of sales and distribution, of composition and recompense, of form and style, of reading and attention, can stagger on much longer.

This is the world we are living in and we can either lie to ourselves about it or we can dive headlong into the new forms and effects that it produces.

I think it was only during the second Lord of the Rings film, The Two Towers, that it hit me. Hang on: I remember this. I remember not liking this.

Like so many others, I was excited by the prospect of the LOTR films. I loved LOTR! I was one of those quite geeky but smart kids who revelled in that imaginary, epic world. I’d read the books several times. It wasn’t until the above moment that I realised I had made this up.

Somewhere between reading the books and reaching my twenties, I had convinced myself that I was the sort of person who liked LOTR, who had read it as a kid, and again as a teenager. Convinced myself utterly. It took the buttock-numbing horror of Sam and Frodo’s long march to remind me that I hated Tolkien almost as much as I hated CS Lewis, and I needed to get out now—and bin the expensive set of LOTR hardbacks I’d recently bought and never opened.

The same impulse can be seen in the endless lies we tell others about ourselves, half-believing them. As a vegetarian (uncaring, unsentimental), I get this from carnivores all the time, it’s oddly pervasive. “Oh, we don’t eat much meat at home.” “I could give up meat.” “I’m almost vegetarian.”

“I don’t watch much TV” is the other one, when you tell people you don’t have a TV. (I don’t have a TV. I watch a bit of TV on the internet. I lie about how much. I’m lying now.)

The most offensive one: “I’d much rather shop at a little local shop.” Bullshit. If you did, there would be no Tescos. But you campaign against it and you petition the council and when it opens you shop there anyway and the little shops die, and you justify it because it’s there now, but that is precisely when action should be taken.

This willful lying to oneself is everywhere; it is particularly evident in attitudes to the future.

Everyone in publishing: “Ebooks will never catch on.” And in the same breath: “but I love my Kindle. It’s so useful for reading manuscripts/reports/whatever.”

Shmuel, a Flickr user and copywriter, put together this excellent bingo card of lies publishers tell themselves, willfully or not. The Ur-comment is at bottom right: “Evidence that doesn’t fit my beliefs is wrong.” What is extraordinary is that this continues even when we ourselves are generating the evidence, when we are our own exceptions.

We prejudge endlessly. Because we have not experienced the emotions that new technologies trigger we assume that they will be less powerful than the emotions we already know. Just because we haven’t had these feelings yet. I love books. But I know that ereading will inspire a whole new range of responses to the written word and I want these too (I am trying to collect them).

I am not saying this is easy. Bill Drummond again:

“Recorded music has run its course. It’s been mined out. It is so 20th Century, like proper money and fossil fuels. Maybe we have the internet to partly thank for this, like we have so much else to thank it for. It has helped speed things up, turning recorded music into this dated thing, like what happened to the German mark during the Weimar republic.” — The17, p.22

“Trying to explain why I think recorded music is in the process of becoming as dated as mosaic or pottery is pretty difficult when for most of us recorded music is the form of artistic communication that has had the most emotional impact on our lives.” — The17, p.145I have to confess too, to stop lying.

I don’t read like I used to—although that’s not necessarily a bad thing. I rarely finish books. I’ve always had a habit of abandoning novels 50-100 pages before the end. I don’t know why, I’ve always done that. I think I’m doing it more and I don’t mind because I think my critical senses have improved and by eradicating book guilt I’ve reached a point where I am happy to cast things aside. I read 5, 10 books at once. I read them on paper and electronically as the mood takes me.

I read with continuous partial attention and I don’t care that I am frequently interrupting my own reading. I despise the discourse that says we are all shallow, that we are all flighty, distracted, not paying attention. I am paying attention, but I am paying attention to everything, and even if my knowledge is fragmented and hard to synthesise it is wider, and it plays in a vaster sphere, than any knowledge that has gone before.

I go through cycles of belief about the future of writing, of publishing, of the written word. But too much is broken to continue to pretend that the models we have become used to, the models of sales and distribution, of composition and recompense, of form and style, of reading and attention, can stagger on much longer.

This is the world we are living in and we can either lie to ourselves about it or we can dive headlong into the new forms and effects that it produces.

An Elixir of Reminding

March 24, 2011

This post is the fourth of seven posts about the future. Caveat lector.

In Jorge Luis Borges’ short story Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius a mysterious encyclopaedia entry leads to the discovery of a new world, a world whose precepts eventually achieve dominance on Earth. The ideas of Tlön manifest themselves in the physical world, until the old world has passed away.

In Tlön, Berkeleian idealism reaches its apogee. Berkeley believed that it was impossible to separate existence and perception: only that which could be directly perceived “existed”, and the rest of the material world was sustained by an omnipresent loving God. In Tlön, God is surplus to requirements. The Tlönian view recognizes perceptions as primary and denies the existence of any underlying reality. Things must be seen to survive: “Occasionally a few birds, a horse perhaps, have saved the ruins of an amphitheater.”

This is the worldview of the Pirahã, as described by Daniel Everett in his book Don’t Sleep There are Snakes: