Video, filmovi i instalacije: divlji zapad i grčka tragedija, ludilo i normalnost, stvarnost i san, mjesečarstvo i institucionalna moć, marginalizirano stanovništvo i maske no drame - šest slijepaca opisuje slona dr. Caligarija.

Oedipus Marshall

Diptych, c-print on Alubond

Each 31 x 53.4 cm (12 1/4 x 21 inch), framed

Ed. of 5 (+ 1 AP)

For his video Oedipus Marshal (2006), a restaging of Sophoclesʼs Oedipus Rex as a Western saga, Javier Téllez worked with amateur actors from the Oasis Clubhouse, a psychatric facility in Grand Junction, Colorado. The lead actor, Aaron Sheley, also cowrote the script with Téllez. In this deliberately paced video, the protagonists wear masks from Japanese Noh theater, calling to mind questions of identity and self-representation.

International filmmaker Javier Tellez has gathered an unusual cast for a film showing Thursday night at the Avalon Theatre.

The son of psychiatrists, Tellez likes to use amateur actors and actresses with mental illnesses to show they’re not all that different from the rest of us.

Set in the historic ghost town of Ashcroft, 14 miles outside of Aspen, “Oedipus Marshall” is a Western based on Sophocles’ Greek tragedy “Oedipus Rex.” The film also incorporates Japanese theater techniques. The actors wear Japanese Noh-masks — 700-year-old wooden painted masks used in Asian theater.

“I think what the director is trying to say, is to concentrate on the message — not the messenger,” said Ken Strychalski, who attended the world premier of the film in Aspen. “The dialogue is so profound.” And the Aspen scenery is magnificent.

The film showed for eight weeks at the Aspen Art Museum, who funded the project.

The Venezuelan-born filmmaker has lived in New York City for the past 10 years, collaborating with consumers of mental health institutions around the world to create short stories depicting the plight of the mentally ill and their interaction with society.

Tellez believes that by working with those who have been pushed to society’s periphery — as is often the case with the mentally ill — he is able to “represent those who have been condemned to invisibility,” while preserving their human dignity.

Tellez came to Grand Junction’s Oasis Clubhouse — a voluntary, recovery-oriented program for people with mental illness issues — to recruit actors for the film. People who participate in Oasis Clubhouse are referred to as members — not clients or patients. The program prefers to focus on who people are — including their strengths, abilities and talents — rather than what they have.

One of the clubhouse members, Aaron Sheley, played the lead role of Oedipus in the movie and co-wrote the script. Sheley showed Tellez one of the scripts he had written over the years, and Tellez asked him to write a Western based on “Oedipus Rex.”

“That specific archetype is embedded in psychology. It’s one I knew well having taken psychology and film theory courses. I tried to adapt the script as close to Oedipus as I could while still keeping the colloquialisms of the old West,” Sheley said. Sheley, 26, is a graduate of the University of Southern California film school.

There are 14 Oasis Clubhouse members in the film. Amorita Randall plays one of the townspeople. She’s an Iraqi war veteran and a survivor of Hurricane Katrina. She has post traumatic stress syndrome.

The actors were transported to Aspen where they worked 14-hour days for two weeks putting together the film. Leaving Grand Junction and everything familiar for two weeks required courage.

“Their challenges were really great,” said Oasis Clubhouse director Alex Sherwood.

“I think it’s equivalent to climbing a 14er,” said Strychalski, who is vocational director of Colorado West Mental Health. “They dealt with rain, snow, sleet, heat and high-altitude sickness. They had physical challenges on top of the mental. It was a real self-affirming thing.”

Members of the clubhouse have problems ranging from extreme sports injuries, war injuries, schizophrenia, depression, anxiety disorders and post traumatic stress syndrome. Some people’s problems are cyclical.

The clubhouse is not a clinical facility.

“It’s a good drop-in place for people who just want to talk, check-in, are having trouble. The Clubhouse has shown to be a good portal,” Strychalski said. “Our job is to ask what we can do to help people in the community to stay well and stay out of crisis, i.e. hospitalization. We try and give our clients support before it escalates to hospitalization.”

The Clubhouse is open Monday-Friday, from 8 a.m.-4 p.m. The facility is funded by Colorado West Mental Health — a regional mental health center.

Sheley tries to stop by the Clubhouse once a week. He said he’s made friends there who will be friends for the rest of his life. “It’s a good place to go and meet people, to get out what’s bothering you, a place to let go of your baggage,” Sheley said.

With so much local interest in the film, Strychalski and Sherwood got permission from the Aspen Art Museum to bring the movie to Grand Junction. The film showing is a benefit for Colorado West Mental Health, in support of the Oasis Clubhouse, and Hilltop’s Life Adjustment Program for traumatically brain-injured adults.

“Oedipus Marshall” will appeal to film buffs, those who follow classical literature, and people who want to see a film made with local actors,” said Strychalski. “It’s an Indie film. I think it could end up at a film festival.”

Another motive in bringing the film to Grand Junction is to increase public awareness of mental illness.

“One in four people will be affected in their lifetime — either by being clinically depressed or so anxious as to start being dysfunctional. Some form of mental illness is the major cause of workplace illness,” Strychalski said.

There will be a reception at 7 p.m. before the showing of the 31-minute film. Following the film will be a panel discussion involving the actors and actresses. - Sharon Sullivan

Caligari and the Sleepwalker

Caligari und der Schlafwandler (Caligari and the Sleepwalker), 2008

Super 16mm film transferred to high-definition video, black and white, 5.1 digital dolby surround, Duration 27' 07'', original version in German with English subtitles

Ed. of 6 (+ 2AP)

"Caligare and the Sleepwalker" was shown for the first time at „Rational/Irrational“ at Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, curated by Valerie Smith, 2009. Inspired by Robert Wiene’s 1920 film classic, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Javier Téllez formed in collaboration with non-professional actors/patients a series of workshops at Vivantes Klinik in Berlin.

The setting for the film takes place in and outside of Erich Mendelsohn’s expressionist Einstein Tower in Potsdam, in the auditorium of Haus der Kulturen der Welt, and at the Klinik. The film opens with a line from Jean Genet’s play "The Blacks: A Clown Show", (Genet was himself inspired by Jean Rouch’s film Les Maîtres Fous), which picks up the ideas of a play within the play and of role reversals in order to question the psychiatric institution and ideas of normalcy and pathology. In the workshops the participants were asked to engage in the creation of fictional narratives based on the original 1920 film. The incorporation of the solar observatory of the Einstein Tower as the main element of the film reflects the multiple optical natures of the cinematic apparatus. Its expressionistic architecture serves as a reference to the original set design of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and helps to catalyze the patients' performances. Through an anthropological approach that merges documentary and fiction film style, performances are rooted in role-playing and improvisation. The film brings out ideas that circulate around concepts of the 'Doppelgänger', subjective perceptions of space, possession, otherness, and schizophrenia.

(based on a text by Valerie Smith, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin 2008)

Javier Téllez’s Caligari and the Sleepwalker uses Robert Wiene’s classic silent movie as the basis for this video installation. This offered the possibility of an interesting take on the story of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari; a film that has been interpreted as a commentary on the German people’s somnambulist response to the rise of the Nazis. The film does reverse that overly misanthropic view but only to replace it with a variant on Nietzschism, whereby it is the somnambulist, Cesare, who is presented as the saviour of mankind.

Set in an observatory cum asylum, the story of Caligari and the Sleepwalker is heavily loaded with clichés about extra-terrestrials (recalling Scott Derrickson’s classic film The Day the Earth Stood Still, though far less sophisticated) and crude anti-professionalism. The argument that runs throughout the film is one that has been the currency of the anti-psychiatry movement since the 1960s and can be found in the ideas of thinkers such as Michel Foucault or R.D. Laing. As a piece of cinema, Caligari and the Sleepwalker is quite interesting, but I feel it has little to offer as a work of art that has anything either original or meaningful to say.

Denis Joe

One of the first works you encounter is Javier Tellez’ film Caligari and the Sleepwalker, 2008. This beautiful, stylish, black and white video is based on Robert Weine’s famous expressionist film Kabinet des Dr Caligari, one of the first films to be recorded inside a real functioning asylum. Where Weine’s film used actors to play patients, Tellez turns this around by using psychiatric patients as actors. The result is a blurring of the boundaries between fiction and reality, the rational and madness. In the film’s opening sequence we see a lone figure delivering a piece to camera. The monologue contains the phrase “When my speech is over everything will be played out here”. This remark sets the pace for an exhibition that is encouraging us to ask questions and allow our thoughts to take shape and unfold outside of our typical systems of perception. - Amy Jones

![Javier Téllez, The Elephant and the Blind Men [Nathon, Khaled, Denise, Steve, Chris and Brandt] Javier Téllez, The Elephant and the Blind Men [Nathon, Khaled, Denise, Steve, Chris and Brandt]](http://www.artnet.com/artwork_images_138114_381043_javier-tellez.jpg)

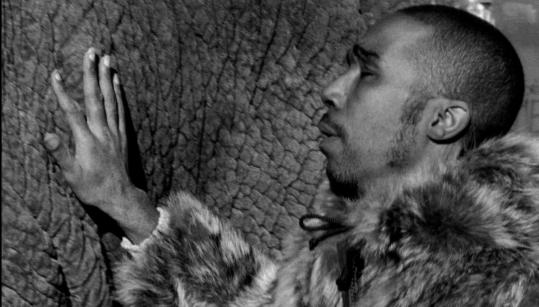

The Elephant and the Blind Men [Steve], 2008

C-print mounted on aluminium, framed

96 x 167 cm (37 3/4 x 65 3/4 inch), framed

Ed. of 5 (+ 2 AP)

This photograph is a portrait of one the respective encounters between the 6 blind persons and the elephant. Also the sculpture which is placed opposite refers to the parable, as Javier Téllez dwells on the different descriptions of the animal. One of them compares the skin with a warm car tyre, another one with a furry sofa cover and a third person with the thick skin of a lizard. According to these specifications, the artist creates an elephant which illustrates how the six blind persons perceive the animal.

The film, in which a woman and five men approach the animal one after another and comment on how they perceive the elephant by touching, smelling and hearing it, is shot in the documentary "cinema verité" style. Now and then, the camera shows close-ups of the elephant’s fissured skin, while the protagonists speak about aspects of their blindness off camera.

Javier Téllez: Letter on the Blind, For the Use of Those Who See

This work is inspired by the Hindu parable “The Blind Men and the Elephant”, which shows how reality is constructed from a clash of different perspectives. The story goes that six blind men all touch different parts of an elephant and then cannot agree on the description of the animal; each one has come away with a different idea, ranging from a tree trunk to a wall, a rope or a palm leaf, depending on whether the part they touched was the elephant’s leg, its side, tail or ear. Téllez’s film is undercut by a paradox: How can one address the experience of blindness through a visual medium? Made in collaboration with a group of blind men from Brooklyn who are brought into physical contact with an elephant for the first time, the piece is structured around the diversity of the participants’ opinions instead of the single voice of a narrator. By multiplying the voices and offsetting the weight of visuality in lieu of the sense of touch and voice, Téllez makes an exploration of subjectivity, a polyphonic guide helping us to contrast vision with other perceptual experiences.

Javier Téllez: Letter on the Blind, For the Use of Those Who See

Javier Téllez engages subject matter that often makes people uncomfortable. Delving into topics such as mental illness and institutional power, the artist critiques contemporary society by questioning passive or harmful notions of normalcy. Téllez’s film Letter on the Blind, For the Use of Those Who See takes its name from an essay by Diderot and is inspired by a famous Indian parable. In the parable, each in a group of blind men touches an elephant and each comes away with a different interpretation of the experience, revealing the fact that no single perspective can be the only truth. Much as the parable suggests, Téllez’s film seeks to give presence to an element of the population marginalized for their differences.

Javier

Téllez, still from Letter on the Blind, For the Use of Those Who See,

2008. Image courtesy Arthouse at the Jones Center and Peter Klichmann

Gallery.

Letter on the Blind performs a difficult exercise in attempting to convey a non-visual reality through visual means. In response to this challenge, Téllez has composed a visually restrained film that gives studied emphasis to sound. The film has a slow, measured pace and is shot in black and white. The decision to forgo color consciously strips the viewer of an element of sight and heightens the awareness of the dichotomy between sight and blindness. Sound clues like urban background noise help describe the setting. The same series of notes from a woodwind instrument play to introduce action, such as when one of the subjects stands to walk toward the elephant. Finally, during the closing credits, each participant’s name is spoken as it appears on screen.

Javier

Téllez, still from Letter on the Blind, For the Use of Those Who See,

2008. Image courtesy Arthouse at the Jones Center and Peter Klichmann

Gallery.

Téllez’s staged encounter does not re-conceive of blindness in the context of sight-driven society. Yet, he does reveal the humanity behind the condition. The visceral, emotive reactions from those touching the animal are particularly poignant and the viewer is made to almost feel a part of the experience. The elephant’s skin is described as feeling, among other things, like ‘a strange fabric’, ‘thick rubber’ and a ‘big plastic wall’. One person finds the experience decidedly unsettling. For another, the elephant is ‘nature’; touch connects him to her ‘beauty’, ‘power’ and ‘tenderness’. Through seemingly candid (although scripted) interaction, blindness is presented as an alternative way of experiencing the world. As one participant states, ‘the visual concept doesn’t exist’ for him. It’s ‘dead’ and he doesn’t wish to have it back.

Javier

Téllez, still from Letter on the Blind, For the Use of Those Who See,

2008. Image courtesy Arthouse at the Jones Center and Peter Klichmann

Gallery. - Kelly Nosari

Hands-on 'Experiments'

Javier Téllez's 'Letter on the Blind' leads a parade of video art at the ICA

I did not go to "Acting Out: Social Experiments in Video" at the Institute of Contemporary Art with high hopes. Years of experience have led me to approach earnestly titled group shows of video art with something less than hopping enthusiasm. Moreover, I do not, as a rule, like watching human beings used in experiments, social or otherwise; it feels like an imposition - on my time, and theirs.

But I suggest you see "Acting Out." It's pretty lean, pretty interesting, prettily installed, and worth the price of admission and the tax on your time for one work alone: a gorgeous, somber, and utterly engrossing 27-minute film by the New York-based Venezuelan Javier Téllez.

The film is called "Letter on the Blind, for the Use of Those Who See." The ponderous title matches the ponderousness of its star: a very docile elephant with exquisitely freckled ears. It stands, unmoving, in the center of a filled-in city swimming pool. One at a time, a series of blind people approach the beast, touch it for a minute or two, and move back to the bench they started out from. That person then reflects on the experience (this is heard in voice-over as the camera homes in on a patch of the elephant's darkly undulant skin) before the next person approaches at the signal of a whistle.

Téllez, who often works with mentally or physically challenged people, is improvising on a theme set out in an Indian parable known as "The Six Blind Men and the Elephant." Six wise but blind men approach an elephant and, each feeling a different part of its anatomy, come to different conclusions about what it is. The moral, presumably, is that one shouldn't leap to wrong-headed conclusions on the basis of scant evidence. But of course, like all the best parables, this one's flexible, and I don't think Téllez has anything particularly didactic in mind. Indeed, on the face of it, his film has all the hallmarks of an undergraduate psychology experiment: How do people react in unknown situations? With fear, or with openness and curiosity?

But what actually takes place in this series of extraordinary encounters between man and beast is so specific, so inimitable, so unpredictable, that it is impossible not to be moved.

One big man approaches confidently. With gliding, cherishing hands, he feels his way over the elephant's skin, finding its ears and face without strain, and whispering tender, awestruck things like "You're beautiful," "It's like the ocean in here," and "I hear you." Afterward, as he reflects in voice-over, he says, "You feel the power and the strength, but you also feel the tenderness." If asked to reflect on its own encounter with this man, you suspect the elephant might say something similar.

The next man, looking somewhat beaten down, approaches tentatively. His hands flap nervously, and he taps tremulously at the elephant, as if half-expecting to touch shards of glass. You feel for him. He is, like the previous man, overwhelmed - but not in a positive way.

After comparing the elephant's skin rather beautifully to "curtains in a mansion," he confesses later that he hadn't been able to tell how wide or tall it was, or in which direction it pointed. Indeed, his main fear was that it would "do some wild things, walk over me or something crazy like that." Who can blame him?

There are some other fascinating films in the show, which was put together by ICA associate curator Jen Mergel. In each case, non-actors have willingly entered into a situation with unforeseen outcomes, and the artist frames and edits what comes to pass.

In one scenario, filmed in Scotland by Phil Collins (no, not that Phil Collins), cash is offered to the person who can laugh the longest. The winner, a young girl, keeps it up for almost two hours, as one by one the contestants around her throw in the towel. The forced hilarity and the sheer physical strain of faking emotion make it exhausting to watch.

Should we take Collins's film as a poignant reflection on the evacuation of people's inner lives in a society perverted by reality TV, as we are encouraged to do? Perhaps. But people have always done crazy things for cash. I thought of the dance marathons held during the Great Depression, when impoverished young couples competed for prize money by dancing for sometimes as long as six weeks without sleeping, "more clinging than moving," as Gertrude Stein put it.

One of the more curious films, "Wild Seeds," is by Yael Bartana, and it shows a group of Israeli teenagers acting out the conflicting roles of settlers and police on a picturesque hilltop in the occupied territories. One group, "the settlers," tries to resist as "the police" force them apart, one by one, and remove them.

The film - which records nothing more than play-acting (although the context is obviously charged) - is a study in perspective. The hand-held camera darts about in the melee, frequently losing focus and only occasionally panning back to give us a wider view of what is going on. We hear only muffled yells, but subtitles on another screen show us what they are saying: "Join the refuseniks, you fascist!," "Ow, you're hurting my arm!," "Burn, you bastard," "A Jew does not deport another Jew," "I can't breathe," and "My glasses!"

The whole thing is silly, but it teeters on the edge of something spooky. It's hard to look away.

The two other films, by Johanna Billing and Artur Zmijewski, are a little less convincing. Billing's "Magical World" presents Croatian children in Zagreb rehearsing the haunting American pop song of the same name. The footage of the rehearsal is interspersed with random shots of everyday life in Zagreb, and the whole thing is intended as a poetic meditation on Croatia's recent efforts to adopt Western ideals. The lyrics - "Why do you want to wake me from such a beautiful dream? Can't you see that I'm sleeping?" - ruffle the calm surface of the film with intimations of something more disquieting, but the film is neither concise nor eloquent enough to involve us.

Zmijewski's film is more confrontational. It shows edited footage of a workshop, organized by Zmijewski himself, in which Polish nationalists, conservative Catholics, Jewish activists, and social leftists were invited to make symbols of their own ideals and to desecrate the symbols of those groups whose views they rejected.

The results are not edifying. We see people who are old enough to know better slicing through slogan-carrying T-shirts with scissors, tossing placards out windows, setting fire to makeshift shrines, and generally hurling abuse at each other.

But of course, none of it feels real. It merely reminds us how histrionic humans can be, forever rehearsing emotions, so that, as Glenway Wescott wrote, "half our life is vague and stormy make-believe."

Animals are different, thank God. In fact, you can't imagine how pleased I was, when I had finished with Zmijewski's film, to go back to my friend the elephant, who was still standing there in abeyance, letting himself be petted by representatives of a very strange species indeed. I sat on the bench in front of him and closed my eyes. - Sebastian Smee

Javier Téllez

Invisible populations; animals, sight, translation and interpretation

A warm tyre, a vulture’s wing without feathers, a plastic wall,

curtains from a mansion: these are descriptions offered by the subjects

of Javier Téllez’ latest film, six blind people confronting a four-ton

metaphor. Letter on the Blind, for the Use of Those Who See

(2007) realizes the famous parable, documenting an encounter between a

group of blind New Yorkers and an Indian elephant. Yet the work is not

so much an allegory as a drama of local perceptions. The five men and

one woman sit on chairs in the centre of an empty, derelict Brooklyn

public swimming-pool and, one by one, come forward to meet the animal.

They share on-the-spot impressions and, in a voice-over, offer

commentary on their separate histories. The stately pace of the film,

keyed to the participants’ careful movements, creates a heightened,

ritual feel. Shot in intense, high-contrast black and white, almost

entirely in close-up, the elephant becomes less a recognizable form than

a tactile expanse, its craggy hide frequently filling the entire

screen. Like the Denis Diderot (1749) essay from which it takes its

title, Téllez’ film commissioned by Creative Time, is an exercise in

translation between the senses, an experiment in synaesthesia.

A warm tyre, a vulture’s wing without feathers, a plastic wall,

curtains from a mansion: these are descriptions offered by the subjects

of Javier Téllez’ latest film, six blind people confronting a four-ton

metaphor. Letter on the Blind, for the Use of Those Who See

(2007) realizes the famous parable, documenting an encounter between a

group of blind New Yorkers and an Indian elephant. Yet the work is not

so much an allegory as a drama of local perceptions. The five men and

one woman sit on chairs in the centre of an empty, derelict Brooklyn

public swimming-pool and, one by one, come forward to meet the animal.

They share on-the-spot impressions and, in a voice-over, offer

commentary on their separate histories. The stately pace of the film,

keyed to the participants’ careful movements, creates a heightened,

ritual feel. Shot in intense, high-contrast black and white, almost

entirely in close-up, the elephant becomes less a recognizable form than

a tactile expanse, its craggy hide frequently filling the entire

screen. Like the Denis Diderot (1749) essay from which it takes its

title, Téllez’ film commissioned by Creative Time, is an exercise in

translation between the senses, an experiment in synaesthesia.It’s a quixotic project, this attempt to visualize the unseen, but an apt one for the Venezuela-born, New York-based Téllez. Over the past decade he has worked with ‘invisible’ populations: the disabled, the poor and those institutionalized for metal illness. That the concept of ‘working with’ is linguistically – and politically – ambiguous is precisely the point. These marginal communities are, essentially, Téllez’ medium. At the same time his film, video and installation-based pieces grow out of and encompass extended collaborative work with his subjects. He walks a tricky, often unsettling line. He flirts with – and yet avoids – the twin perils of exploitation and do-gooder-ism, deriving ethics and aesthetics from the situation in which he finds himself.

If it’s possible to be born into such a role, Téllez’ autobiography would qualify him. The son of two psychiatrists, he grew up tagging along to the institution his father supervised. At a yearly festival there were beauty contests: doctors and patients would, for a day, exchange uniforms. Such carnivalesque reversals remain a powerful trope in Téllez’ work. One Flew over the Void (Balla perdida) (2005) – created for inSite, a biennial event straddling the Mexico/US border – is literally a carnival. With residents of a Mexican mental institution the artist developed a public spectacle – part circus, part protest march – around the theme of borders, literal and metaphorical. The rally culminated in a professional human cannonball being shot over the fence dividing Tijuana and San Diego.

Bizarrely resonant images such as this, simultaneously absurd and heady with reference, form the core of Téllez’ projects. In the video El león de Caracas (The Lion of Caracas, 2002), a stuffed and mounted lion makes its way down the vertiginous steps of a hillside Caracas shanty town, borne by four uniformed police officers. The lion, symbol of the Venezuelan capital, here takes the place of a Holy Week saint, while the procession also recalls the all too common ritual of police carrying a corpse out of the ranchitos. As giggling children rush forward to touch the immobile animal, the cops shuffle awkwardly in the background, all enlisted in a strange portrait of power and powerlessness. For You Are Here (2002) Téllez presented patients of an appallingly medieval Venezuelan mental institution with an enormous inflatable ball, a super-sized version of a stuffed cat toy. Rolling it through the labyrinthine corridors and out into the courtyard, they somehow spontaneously conspire (after many harrowing minutes of the blackest of slapstick comedy) to push the huge object over the wall, effecting its escape.

La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (Rozelle Hospital) (The Passion of Joan of Arc, Rozelle Hospital, 2004) offers a more elaborate intervention. Téllez spent a month in workshops with a group of 12 women at an institution in Sydney. After viewing the Carl Dreyer film La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928) the patients wrote new intertitles. Unsurprisingly, they reconceived it as the story of ‘JDA’, committed for believing she was Joan of Arc, ‘suffering from grandiose visions and auditory hallucinations’. Presented as a two-channel piece, the revamped silent film is accompanied by a series of intimate interviews with the co-creators. One woman conducts a dialogue with a marionette therapist, perfectly ventriloquizing the language of the professional mental health worker; another reads journal entries detailing her electroshock treatments. A young woman offers a giddy monologue of her institutionalization, while explaining her knowledge of Morse code through a past life memory. Suddenly, she breaks into song, a moving hymn proclaiming her resistance to rules and bureaucracy.

In the words of British psychologist Adam Phillips, madness ‘is defined, so to speak, by what it elicits in others’. And it is precisely through definition that the so-called mad are contained, administered and treated, in ways that are more or less useful, more or less humane. Téllez’ work manages to escape this logic: it is designed to elicit a response while circumventing the structure of definition altogether. He offers nothing as positivist as a ‘position’ on mental illness, and certainly nothing in the way of a cure. Rather, his odd and compelling spectacles embrace the irrational as a method of translation pressed to its limits. They are a series of letters on the mad, for the use of those who think themselves sane.- Steven Stern

Letter on the Blind, For the Use of Those Who See

The

story of the six blind men and the elephant, which serves as the

fulcrum for Javier Téllez’s installation at Arthouse, presents one of

those platitudes that at first seems incredibly obvious but becomes

chillingly prescient with a little investigation. Plenty of versions

exist with plenty of diverging plot points, but the gist of the story is

that six blind men are tasked with identifying an elephant by touch

alone. Because the elephant is an enormous and varied animal, each man

makes a wildly different guess based on which part of the elephant he

approaches. The man touching the tusk imagines the animal to be a sewer

pipe, while the man who touches its towering side thinks it most likely a

wall. Though we know that they have not accurately described the

elephant’s complete corporeal state, none of their perceptions are

incorrect. The elephant’s nature is a composite made inscrutable by a

limited perspective.

Javier Téllez, Letter on the Blind, For the Use of Those Who See (still), 2007; 16mm film transferred to high-definition video with sound; courtesy Arthouse at the Jones Center.

The story’s implication that we’re incapable of perceiving all but the

most superficial aspects of some phenomenal object before us is scary.

Or hopeful, if, like me, you find the idea of a universal perceptive

limitation vaguely comforting. Rather than merely insisting on the

legitimacy of diverging perspectives, the story presents us with a means

to gather in our ignorance.

In Letter on the Blind, For the Use of Those Who See, Téllez abandons limitation as an essential facet of the fable. His film presents six blind people confronting an elephant in an abandoned courtyard of Brooklyn’s McCarren Park swimming pool. Accompanied by a spare panpipe-like soundtrack and filmed in black-and-white, each person approaches the elephant and feels it. After each is seated, Téllez cuts in with a slow and sustained shot of the animal’s skin, framed so tight that it seems more an abstract image—almost a contour map—while in voiceover, the person who just touched the elephant describes some personal take on experiencing blindness. These moments are arresting and dreamy, made even more so because the elephant’s breathing causes the background to shift slowly. Narrowing the viewer’s gaze to an abstract image presents a sly visual analog to the subjects’ descriptions of their condition.

In spite of its earnestness as a walk-two-moons-in-another-man’s-moccasins narrative, the film arrives at some fairly banal assertions. Each person who approaches the elephant self-narrates while touching it and walking around it slowly, but very little of what they say is substantially different from what any person might say when first encountering a magnificent and strange animal. The essential riddle at the heart of the original story—that we cannot ever know the extent of the reality presented us—is here circumvented and defanged because the documentary’s subjects already knew that they would encounter an elephant. They approach the elephant, awed by its size and the texture of its skin, but they only speak about blindness during close-up shots that are separate from their interactions; even then, these observations don’t relate to touching an elephant. The film falls short by presenting blindness as particular to the blind instead of as a condition endemic to human experience. Limitation as a condition of the original story has been made merely literal. Instead of concerning itself with what the elephant is, Téllez’s film focuses on what the elephant resembles. The difference between these figures may seem slight, but it contains all the difference between magic—replacing one thing with another—and description.

Javier Téllez, Letter on the Blind, For the Use of Those Who See (still), 2007; 16mm film transferred to high-definition video with sound; courtesy Arthouse at the Jones Center.

Invoking the classic story without corresponding to its conditions

incites a kind of impatience that otherwise would not exist. When an

idea so freighted with potential connections is carried out, it’s

annoying that there’s little surprise or generative tension in the

result. It doesn’t help that the work’s title assumes an explanatory

stance, with its invocation of a letter about or from the blind sent for

the use of the sighted. Téllez lists the six subjects of the film as

“collaborators;” his intention is to grant them participatory status and

the wall text accompanying the installation makes much of the fact that

the six of them speak their names during the credits, inhabiting the

piece vocally since they cannot seemingly enter it any other way.

Unfortunately, this only highlights the fact that the film gives them

few other opportunities to truly collaborate with Téllez. It’s

ultimately unclear what use those who see are meant to make of the work.

Even so, footage of a person (sighted or not) touching an elephant for the first time is compelling stuff. The soundtrack’s restraint gives it a narrative presence; the repeated phrase that summons each person to the elephant and signals their return to their seats implies an injunction to participate in a ritual, as if gathering sensory experience is part of a longstanding human pageant. That more humble sentiment propels this film in spite of its educational trappings.- S.E. Smith

Javier Téllez, Letter on the Blind, For the Use of Those Who See (still), 2007; 16mm film transferred to high-definition video with sound; courtesy Arthouse at the Jones Center.

In Letter on the Blind, For the Use of Those Who See, Téllez abandons limitation as an essential facet of the fable. His film presents six blind people confronting an elephant in an abandoned courtyard of Brooklyn’s McCarren Park swimming pool. Accompanied by a spare panpipe-like soundtrack and filmed in black-and-white, each person approaches the elephant and feels it. After each is seated, Téllez cuts in with a slow and sustained shot of the animal’s skin, framed so tight that it seems more an abstract image—almost a contour map—while in voiceover, the person who just touched the elephant describes some personal take on experiencing blindness. These moments are arresting and dreamy, made even more so because the elephant’s breathing causes the background to shift slowly. Narrowing the viewer’s gaze to an abstract image presents a sly visual analog to the subjects’ descriptions of their condition.

In spite of its earnestness as a walk-two-moons-in-another-man’s-moccasins narrative, the film arrives at some fairly banal assertions. Each person who approaches the elephant self-narrates while touching it and walking around it slowly, but very little of what they say is substantially different from what any person might say when first encountering a magnificent and strange animal. The essential riddle at the heart of the original story—that we cannot ever know the extent of the reality presented us—is here circumvented and defanged because the documentary’s subjects already knew that they would encounter an elephant. They approach the elephant, awed by its size and the texture of its skin, but they only speak about blindness during close-up shots that are separate from their interactions; even then, these observations don’t relate to touching an elephant. The film falls short by presenting blindness as particular to the blind instead of as a condition endemic to human experience. Limitation as a condition of the original story has been made merely literal. Instead of concerning itself with what the elephant is, Téllez’s film focuses on what the elephant resembles. The difference between these figures may seem slight, but it contains all the difference between magic—replacing one thing with another—and description.

Javier Téllez, Letter on the Blind, For the Use of Those Who See (still), 2007; 16mm film transferred to high-definition video with sound; courtesy Arthouse at the Jones Center.

Even so, footage of a person (sighted or not) touching an elephant for the first time is compelling stuff. The soundtrack’s restraint gives it a narrative presence; the repeated phrase that summons each person to the elephant and signals their return to their seats implies an injunction to participate in a ritual, as if gathering sensory experience is part of a longstanding human pageant. That more humble sentiment propels this film in spite of its educational trappings.- S.E. Smith

Javier Téllez by

Oedipus Marshal, 2006, still from single-channel video. 30 minutes. Comissioned by Aspen Art Museum, Aspen. All images courtesy of the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich.

Téllez and I once played telephone with tin cans perched on trees at the Utopia Station site for the 50th Venice Biennale, but, for the following interview, we discussed his increasingly depurated film projects—Oedipus Marshal (2006), (2007), and Caligari and the Sleepwalker (2008)—over the less cumbersome and more contemporary mediums of the telephone, email, and Skype.

Pedro Reyes Where should we begin? At the beginning or at the end?

Javier Téllez In the middle.

PR Which part is the middle?

JT The middle would be the present.

PR Javier, in the development of your work over the past 15 or 20 years, you’d always used video, but lately your work has consisted of films.

JT I’ve always wanted to make films. My grandfather founded one of the first movie theaters in Venezuela in 1911: the Capitol Theater in Turmero, the small town where my mother was born. We’d visit often, so I spent part of my childhood in the projection booth. Since I was a kid, I would film what I saw around me with the old Bell and Howell camera my dad gave me. Later I studied film and acquired a Super-8 camera so that I could make movies using my friends as actors. In the ’90s, I used video because it was a more accessible medium. It’s only in the past five years that I’ve managed to create films. The brilliant Cain-Abel image Godard used in Sauve qui peut explains the relationship between film and video beautifully. The truth is that these days, it’s impossible to conceive of the one without the other. Though video is immediate and readily lends itself to the urgency that imbues many of my projects, film, on the other hand, possesses an unquestionable element of “reality.” That is, film as a medium is constituted as “reality” by being both exposed, or developed, and exposed, or shown, before an audience. I prefer to make movies on film although, in the end, for practical reasons, I might transfer them to video. For me, film “incarnates.” As a medium it registers precisely the idea with which we began this conversation—being in the middle, in the here and now.

PR In Godard’s Le petit soldat, while the protagonist is taking pictures of a character named Veronica, he utters the now famous quote: “Photography is truth. And cinema is truth 24 frames a second.” The etymology of the name Veronica is “the true image,” and it refers to the cloak with which Saint Veronica wiped the face of Christ during the Passion. His image remained on the cloak—we could say it’s the first Polaroid in history. Might it be that the chemical stigmata that light leaves on the negative is what makes cinema true?

JT Cinema is the wound and the stain, no doubt, but the stain in motion! “If something is to stay in memory, it must be burned in,” Nietzsche wrote in his Genealogy of Morals. Film burns this truth 24 times a second. The Council of Nicea recounts that a certain Harrasin of Gabala drove a nail into the eye of an icon, and instantly lost one of his own. This was perhaps the first antecedent of Vertov and his Kino-Eye, or the celebrated image of Luis Buñuel. Yet another story of cinema before cinema, protocinema.

Also, the time and effort that completing a cinematographic production requires is a sort of Passion. In order to produce the icon, we need to bear the cross that precedes the epiphany. And the successive appearance of the body on the screen is, without a doubt, a form of resurrection. Some great 20th-century filmmakers have been interested in depicting the epiphany of reality on celluloid: Buñuel, Pier Paolo Pasolini, and, especially, Roberto Rossellini. All of them have been under the theoretical influence of André Bazin, and had a relationship to Catholicism and the permissiveness of the image that opened up with the Counter-Reformation. I’ve always seen a continuation of the chapter in art history that Caravaggio and the Spanish Golden Age painters opened in the films by these directors.

PR So going to the cinema, then, would be a sort of sacramental act.

JT It could even be seen as a form of Eucharist. The absorption of static images on the spectator’s retina, read by the nervous system as images in movement, is a sort of transubstantiation of the bodies represented on the screen.

Caligari and the Sleepwalker, 2008, still from high-definition video. 27 minutes, 7 seconds. Comissioned by Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin.

PR In your last film, Caligari and the Sleepwalker, you include a scene of the actors attending a screening of the same film they’ll reenact: the 1920 Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari by Robert Wiene. Talk about the phenomenon of somnambulism in the film. Are there analagous relationships between wakefulness and sleep, reason and common sense, life and film?

JT Any film lover is fascinated by the double mechanism that registers images and projects them to create the illusion of movement. The cinematographic mechanism’s hypnotizing quality is one of the fundamental themes of Caligari and the Sonambulist. Curator Valerie Smith invited me to make a film in Berlin that would be shown in the exhibition Rational/Irrational at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt. As is my usual practice, I decided to make a film in collaboration with the patients of a local psychiatric institution. The two elements I used as springboards for my collaboration with the patients were the Wiene film and Mendelsohn’s observatory Einsteinturm (the Einstein Tower). Both icons of German Expressionism were produced simultaneously in Potsdam at the beginning of the ’20s and constitute the swan song of the avant-garde movement. So, I watched the film with the patients and invited them to make a new version of it primarily inside Mendelsohn’s building.

Hypnosis is one of the themes in Wiene’s Caligari, as is madness—it contains one of the first cinematograpic representations of a psychiatric hosital. This is what led me to present it to the patients in the first place. The way cinema relates to hypnosis and spiritism has been present from the very first texts that describe the perception of images in motion. The history of modern psychiatry, too, is linked to hypnosis via Charcot and La Salpêtrière. It’s only natural that these themes reappear in a project that directly engages a film like Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. We were particularly interested in exploring visual and auditory hallucination.

PR Mendelsohn’s building, a solar observatory that is surprisingly smaller than the idealized image we see in architecture books, operates in your film as a magician’s tower or an extraterrestrial space station.

JT When I inititally proposed the idea of Mendelsohn’s tower as an image to the patients, they developed a narrative that strayed from the original story of Dr. Caligari’s cabinet. From the horror genre of the original film, we moved toward science fiction. The telescope that inhabits Mendelsohn’s building—we could say that the whole building is the apparatus—becomes a machine that produces the narrative of delirium. It’s a bit like in Adolfo Bioy Casares’s story “The Invention of Morel,” where a quasi-cinematic machine produces simulacra of characters and situations inside an abandoned building.

In his classic study of hallucinations, On the Origin of the “Influencing Machine” in Schizophrenia, the psychoanalyst Viktor Tausk, who was a colleague of Freud’s, describes a psychic device that he calls “the schizophrenic influencing machine.” It’s as if a machine caused patients to experience flat visual hallucinations. A sort of magic lantern, the machine creates or removes thoughts via mystical rays or forces that also produce involuntary movements in the patient’s body, discharges of semen, and erections. The schizophrenic patient describes these sensations as manifestations of electrical or magnetic energies. Tausk’s writings on his patient’s delusions could easily fit in a reader of what’s been called the “cinematographic apparatus.” Also fundamental are the detailed descriptions by James Tilly Matthews, a patient at an English insane asylum at the turn of the 18th century, of the imaginary “air loom machine” used by villains to control people, and Memoirs of My Nervous Illness by Daniel Paul Schreber, a patient of Freud’s. I see these as a sort of counter-technology, constructed from within mental illness, that challenge Bentham’s Panopticon and the other control apparatuses abounding in the history of psychiatry.

Mendelsohn’s fantastic solar observatory became central to our narrative because it functioned as a schizophrenic machine allowing hallucinations to be transmitted through contagion or projection. All of this, in short, as a metaphor for film.

Caligari and the Sleepwalker, 2008, still from high-definition video.

PR Is film a phenomenon similar to lucid dreaming, where one takes control of one’s dream?

JT: For sure film and dreams are siblings. With Caligari and the Somnambulist, I’d like for something akin to Chuang Tsu’s dream of the butterfly to occur.

PR In your film the patients are simultaneously actors and spectators of their own action. Given that you filmed them watching the movie you made with them and then included this footage in a subsequent version of the film, is this split within the ego an analogy for schizophrenia?

JT As the patients watch the film, they make comments that later the spectators of my film experience non-diegetically as voice-overs—the power of the disembodied voice is characteristic of auditory hallucination. And the exchange of roles between spectators and participants in my film continues with the carnivalesque spirit of all the work I develop in collaboration with people who are mentally ill.

PR What about the chalkboards on which the patients write their own dialogue? They are a resource you’ve taken from silent films, but in what almost amounts to a Brechtian break, in your films they’re held by the actors themselves.

JT Chalkboards are a constant in my films. They reaffirm the way that cinema, as a medium, is inscription—a type of mystic writing pad, a palimpsest reaffirming the pedagogical nature of the work of destigmatization. They can be read literally as an image that gives the patients voice by introducing the canceled or excluded language of those who live with mental illness within Logos. Also, the introduction of written language within the context of visual representation represents a distancing from the passive consumption of the image in motion.

PR In your Caligari, and also in your film Oedipus Marshal, the Western you made in a ghost town near Aspen, Colorado in collaboration with patients of a nearby psychiatric hospital, you work with the suppression of a particular resource. In Caligari, it was the voice; in Oedipus Marshal, facial expressions were substituted with masks.

JT Voice-overs, or disembodied voices, are a recurring element in my films; yet the idea of hearing voices is something that patients bring to the narratives on their own, without my having instigated it. The case of Oedipus Marshal was particularly interesting to me, since the voices in the auditory hallucinations had been inspired by the role of the chorus in classical tragedy. And in my film Letter on The Blind For Those Of Us Who See, the voice, per force, was the principal medium of collaboration with the blind people.

Caligari and the Sleepwalker, 2008, still from high-definition video.

PR You’ve told me that prior to beginning a project you hold workshops where you sit with patients to discuss their ideas, develop the plot of the films, and make casting decisions with them. Aside from technique, what makes your Caligari unique to me is the collective playwriting process.

JT Each project is specific, since it is the result of collaborating with particular people. Of course, I accumulate experience and learn from each project. Normally, before beginning a new project, I show my earlier films to the patients I’m going to work with: this also might generate a certain sense of continuity.

PR The Brazilian director Augusto Boal said that Aristotle promoted the use of the chorus in classical tragedy because it relieved the audience from their need to express themselves in the face of a tragedy’s unfolding: “You don’t need to express your opinion; the chorus will do it for you.” When you open the door to the patient’s participation, in terms of playwriting, are you allowing for an array of different outcomes? Are you interested in the possibility of reinventing drama?

JT I still have my doubts about Boal. I think that, in the end, his reading of Aristotle’s Poetics is limited, as is his formulation of a “theater of the oppressed,” which doesn’t successfully depart from a didactic model. Boal’s experiments seem to seek to demonstrate the therapist’s mastery, and this might be a continuation of Jacob Levi Moreno’s psychodrama. It’s necessary to place Antonin Artaud up against Brecht; and up against Boal, to posit more relevant experiences such as Grotowski and The Living Theater, or the invisible theater of happenings. What we find in these is the unscripted creation of uncontrolled performative situations where the limits of reality and theater are dissolved through catharsis, collective rituals, the spectator’s active involvement, and the carnavalesque. Perhaps Boal isn’t aware of the true Dionysian spirit of Greek tragedy when he distances himself from the most interesting theatrical experiment of the first half of the 20th century: Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty.

Oedipus Marshal, 2006, still from single-channel video.

PR Regarding psychodrama, Jacob Levi Moreno was focused on the idea of “training spontaneity”: the therapeutic role of creativity in the impromptu creation of a play. In film production, the threshold of spontaneity is reduced, since ensuring the image’s quality requires a certain control. Can you give me an example of an element that arose in the sessions with the patients that you later incorporated into Oedipus Marshal as you were making the film?

JT The script is always written with the patients, but in their performances of it there are always variations and surprises, especially since we’re talking about people who have never had professional experience as actors. It’s inevitable that they’ll produce unexpected results. I’m interested in working right on that line where patients will continue to be themselves but at the same time will be possessed by the characters they’ve created. My projects—like all cinema, perhaps—exist halfway between documentary and fiction. Spontaneity might be read in a variety of ways. I agree with Robert Bresson when he argues that theater in its classical form destroys the spontaneity of actors given that their acting must be repeated and rehearsed innumerable times. The cinematographic record, on the other hand, is unique—it’s the record of an instant that only repeats when it is projected.

Oedipus Marshal, 2006, still from single-channel video. 30 minutes. Comissioned by Aspen Art Museum, Aspen.

PR One question I genuinely ask myself in relation to your work has to do with the notion of agency. Placards and blackboards provide the patients with agency.

JT They’re props in the sense that Artaud uses them in Theater of Cruelty—props that become meaningful in their own right, beyond their functional value within the plot. It’s a kind of bricolage, where patients can interpret all kinds of diverse elements when talking about their lived experiences.

In the workshops the patients become a collective. We read a film, a building, a fable, or a Greek tragedy as texts—this was the case for Caligari and the Somnambulist, as I explained, and also for my version of The Passion of Joan of Arc, and Oedipus Marshal. This text I bring to the patients functions as the connector that might allow for collective agency—I often work with patients who don’t know each other very well, so starting off reading a text is very helpful. For Oedipus Marshal, we selected Sophocles’s tragedy alongside the genre of the Western (the movie was filmed in Colorado) as points of departure. I’m deeply interested in how the patients translate the original narrative into their own reality. The Greek tragedy underwent a process of metamorphosis when it was adapted to the specific circumstances of the American West and to the realm of mental illness. Patients read the figure of Oedipus as a schizophrenic instead of as a Freudian neurotic. The voices of the Greek chorus, in our narrative, became the main character’s auditory hallucinations.

We used a range of genres—Westerns, Japanese Noh theater, and Greek tragedy—not to create parodies but rather as containers for new meanings that might be produced via the strategies of the bricoleur.

PR It’s fascinating that you’d distance yourself from parody. Parody makes fun of a genre at the same time it uses its resources. It seems to me that your work is closer to a theory of metatheater—or, in your case, metacinema. In your films, our reading of the actors’ work cannot be disassociated from our knowledge of their mental condition. Are you interested in Peter Brook’s The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade?

JT A person living with mental illness lives Rimbaud’s “I am an Other.” It’s not difficult for him or her to reach a state of possession. Marat/Sade, or more precisely, what we imagine Sade’s theatrical representations might have been based on Peter Weiss’s play are an interesting phenomenon, since they operate within an exchange of roles between spectator and actor. This also relates to the carnivalesque spectacle in which the world was turned upside down: the medieval theatrical representation of the celebration of madmen using entire towns as their stage.

The presence of carnival within my work comes from the visits I made during my childhood to the carnivals of the psychiatric hospital of Barbula, where my father worked as a psychiatrist. Patients there would trade their uniforms for the hygenic white coats of the doctors. This image, “burned in memory,” has stayed with me for the rest of my life, and has become one of the guiding images of my work.

Caligari and the Sleepwalker, 2008, installation with single-channel projection. Installation shot of Mind the Gap, Kunsthaus Baselland, Muttenz, 2009. Photo by Viktor Kolibal.

PR I’ve asked you before if you consider your work to be therapeutic. You responded that more than curing crazy people, you are interested in curing sane people of their sanity.

JT The cure for the sane and the cure for the sick: negation and affirmation at the same time. Madness is situated beyond language, it shares a liminal condition with art.

The problem with therapeutic psychodrama, like the one proposed by Jacob Levi Moreno, is that it continues to enact the privileged position of the therapist, of the one who administers the cure. I prefer a truly dialogic method, an inter-subjective model in which the encounter with the other might be possible without the eradication of difference. I’m thinking concretely about the films of Jean Rouch, who’s been a huge influence on my work. In other words, I’d prefer my practice be seen as a bridge, and not as a path to a goal.

PR Letter on the Blind for the Use of Those Who See is undoubtedly a film about inter-subjectivity.

JT It presented a particular problem—

PR Epistemologically?

JT And phenomenologically, too: how to make a film in collaboration with blind people, some of whom had never seen in their lives. The solution came from the voice and from touch. The camera recorded the tactile experiences of the blind as they touched the body of an elephant, but the images were later edited with recorded descriptions from the blind people. The film’s viewer, then, was located within the point of view of the person who cannot see (a blind spot for sure). For a while I’d been wanting to make a film about blindness as homage to my mother, who gradually lost her vision during the last years of her life.

Letter on the Blind for the Use of Those Who See, 2007, still from high-definition video. 27 minutes, 36 seconds. Comissioned by Creative Time, New York.

PR The premise of the film originates in the Hindu fable “The Blind Men and the Elephant.”

JT The project for the film started off with the Indian fable of the elephant and the six blind men—the Eastern counterpart to our Platonic cave, and another history of protocinema. Six blind men attempt to recognize a pachyderm. Each one touches a different part of the animal, so therefore they cannot reach an agreement about the elephant’s characteristics. The premise of the parable is erroneous given that the blind men were not allowed to touch the animal’s entire body—one of my sightless collaborators highlighted this during the making of the film. For me, the film itself becomes the elephant that the spectators, those who see, have to recognize despite their limitations. Their main limitation is that since they can’t stop seeing, they cannot access blindness.

PR There’s a phrase from Diderot saying: “If you want me to believe in God, you must make me touch him.” Are you interested in Diderot’s rationalism?

JT No, we only took the title of our film from Diderot’s text. We might touch the veil, but not the body of God. This reminds me of that classic story about trompe l’oeil retold by Pliny the Elder: the rivalry between the painters Parrhasius and Zeuxis was resolved through a competition. Zeuxis asks Parrhasius to unveil his painting, soon realizing that there is no veil to lift; what he’s seeing is represented within the painting itself. Parrhasius’s indisputable mastery is demonstrated. This is a very beautiful story about the illusory nature of all representation. As illusionists, which we are by nature, it’s our task to signal the limits of language itself: negation and affirmation at the same time.

Letter on the Blind for the Use of Those Who See, 2007, still from high-definition video.

PR On the topic of tricks, let’s talk about ha-ha walls.

JT It’s fascinating that you mention them. In Sydney, in the Rozelle hospital where I shot The Passion of Jeanne d’Arc, I found some original remains of ha-ha walls built around the asylum. The ha-ha wall is an important architectural element in the renovation of psychiatric institutions, as it permits the inmates of the institution an illusory contemplation of the landscape, and yet at the same time isolates them from the rest of society. The ha-ha is thus as much a sophisticated mechanism of control as Bentham’s Panopticon.

As for tricks, have you heard the joke about the hole in the hospital wall? A flaneur is walking around the outer wall of a psychiatric institution, sees a hole in the wall, and hears that on the other side someone is repeating “One hundred, one hundred, one hundred . . .” The flaneur peeks through the hole and sees a patient behind the wall who sticks an awl through the hole, and pulls out the prier’s eye, and begins repeating “One hundred and one, one hundred and one, one hundred and one . . .”

PR Ha!

JT Seems like today we’re paying homage to Don Luis, don’t you think?

PR Buñuel? Oh yes. In My Last Sigh he says that his lack of interest in science is due to its limited ability to explain those matters of deepest concern to him—dreams and laughter, for instance. If you explain a joke, it ceases to be funny. There’s a type of knowledge that we can only access through art, or artifice.

JT In that sense, the best translation of the term trompe l’oeil would be eye trap.

PR So speaking of walls, let’s return to architecture.

JT One of the recurring thematic concerns in my work with people living with mental illness is architecture. The architecture of confinement is obviously an everyday concern for those who experience it or have been institutionalized. The image of the house keeps reapparing in their visual representations. A person who is mentally ill is basically a homeless person forced into an interior exile by the rest of society—no wonder Oedipus functioned so perfectly as the alter ego of my collaborators. The psychiatric institution is a home forced upon the patient, an architectural straitjacket that the patient must survive in or transgress. This is why I’ve been interested in making architectural works in the past: the gigantic birdhouse Bedlam from 1999; Liftoff, from 2001, which is another birdhouse designed by a patient as a hybrid between a trap and a gigantic loudspeaker; Choreutics, from 2001, a gigantic spider web in the form of a fish trap; and finally, in the installation version of Caligari and the Somnambulist, a pavilion made of chalkboards serving as a projection room. The image of the trap inverts the institutional trap in these works. Somehow it responds to the image of the burrow in Kafka, in which as Deleuze and Guattari claim, “Only the principle of multiple entrances prevents the introduction of the enemy.”

PR We started out talking about Godard, who once said: “A story should have a beginning, a middle, and an end . . . but not necessarily in that order.” We’ve already talked about the present and the past. Can you tell me what you plan to do in the future?

JT . . .

Madness is the Language of the Excluded,” An interview with Javier Téllez by Michèle Faguet and Cristóbal Lehyt, C Magazine 92, Toronto, Winter 2006

The interview format is most fitting for a discussion of the recent work of Javier Téllez given that he is so articulate and forthcoming about the complicated set of references—historical, literary, cultural, personal—that have informed his practice. Téllez is earnest in his attempt to engage in an ethical, consequential manner with communities of individuals who live outside of the models of normative behavior that define the parameters of a ‘sane’ society but that are constantly shifting in relation to the ideological structures that determine this social order.

MF&

CL: When speaking about your work you have often made reference to the

phonetic similarity between museum and mausoleum written about by

Adorno. Your own proximity to and interest in psychiatric practice has

resulted in a series of works that extracts, in an almost archaeological

manner, objects from the sterile, white hospital wards that make up the

visual landscape of the mentally ill, and inserts these objects into

the pristine white cube of the museum. Can you elaborate on what you see

to be the processes of selection and exclusion common to both

psychiatric and curatorial practices?

This inclusion obviously takes place within a framework that includes the conditions of distribution and reception of the art system. In the end it is about working in collaboration with other people and I never pretend not to be visible in the discouse, but the work is articulated in the dialogue between my subjectivity and their subjectivities.

The

theatrical elements we use as props—costumes and masks—are related to

the Carnival which is an important axis of my work. The use of the

carnivalesque is related to its potential to create a collective

experience that confuses the roles of actors and spectators, giving

political agency to a community that is fragmented within the

psychiatric institution. I have always been interested in the subversive

element of transgression inherent to the festive celebration, even

prior to reading Bakhtin, a writer who has been very influential in my

thinking. My relationship to the carnival comes from my childhood: while

growing up in Venezuela my father often took us to visit the mental

hospital were he worked as a psychiatrist. Every year the staff and

patients there organized a carnival with a parade, costumes,

decorations, and a beauty contest. Almost everybody in the institution

participated in the event. I have one very vivid memory of seeing

patients and psychiatrists exchanging their respective uniforms. This

experience is very significant to me, because it allowed me to see, from

a very young age, this sort of symbolic interchange and role-playing as

a model to transgress the notions of ‘normal’ and ‘pathological’

behavior and the power relations inherent to the psychiatric

institution. -michiacevedo.blogspot.com/

Where is the difference between the Maid of Orléans and a patient diagnosed with a schizophrenic psychosis? In the waning Middle Ages, the French farmer’s daughter Joan of Arc claimed to have visions from God urging her to free her homeland from English domination. Provided with the king’s army, she then proceeded to expel the English from Orléans. (Later, of course, when she was no longer needed, she was executed for heresy). People with schizophrenic disorders usually hear voices, too, but unlike Joan of Arc, they don’t become heroes of history.

However, the question with which we began has perhaps been wrongly posed. Our inclination to prove that Joan of Arc did not really hear the voice of God, but rather suffered from delusions does not hit the crux of a story that is based primarily on a woman’s emancipation from her designated social role. Javier Téllez has thus conceived another scenario by searching for similarities between Joan of Arc and the schizophrenic. Over the course of several weeks, the artist engaged intensively with several patients from a women’s psychiatric clinic in Sydney, Australia. The women offered insight into their illnesses and sensibilities in front of the camera. Then, together with the artist, they restaged the famous silent film The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) by Danish filmmaker Carl Theodor Dreyer. The women in the film replaced the original text with their own ideas and wordings in order to be able to identify with Joan of Arc, who then stood both as an example of and as a point of reference for their own suffering.

Neurotic disorders are more easily tolerated in modern society than psychotic disorders because, to greatly simplify the situation, neurotics are aware of their disorder and able to reflect upon it. People suffering from psychoses, in contrast, are incapable of distinguishing their inner world (e.g., hearing voices) from the surrounding reality, and subsequently come to regard the outer world as hostile. Thus unable to take responsibility for itself, the ill subject feels like a victim of the outside world and restricts its activity to passive suffering. According to Sigmund Freud, neurosis can be understood as an illness of guilt. However, psychosis, along with depression, are seen as illnesses of responsibility, in which feelings of inadequacy dominate over those of guilt, or in which feelings of guilt are experienced as a kind of inadequacy (see Alain Ehrenberg’s work). Our current understanding of “mental health” interweaves physical health and social behavior. Those no longer capable of or willing to engage in “normal” social behavior are categorized as ill. They are considered incapable of conforming their emotions and morality to the expectations of others. Téllez’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (Rozelle Hospital) observes women who could not meet the requirements of their social environment and who consequently had to renounce their own social needs. Their depression is a symptom of their failure in the world.

By echoing Joan of Arc’s story, Téllez’s work also establishes a connection with society’s inability to deal with the needs and fears of the individual. As a consequence, individuals are tacitly ostracized. The depressions from which all patients suffer, regardless of their different diagnoses, can be understood symbolically as their capitulation to the ever increasing requirements of a world that demands, first and foremost, that we be responsible, flexible, active, and socially competent.

http://www.zkm.de/betweentwodeaths/en/art/tel_txt.html

Javier Téllez

La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc (Rozelle Hospital, Sydney), 2004

two channel projection

video stills from Twelve and a Marionette and La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc

Artaud’s Cave, 2012

Installation, cave elements and one single-channel film projection

Ed. of 6 of La Conquista De México, 16:9, color, sound, 45 min.

Unique

Inspired by Antonin Artaud‘s legendary 1936 trip to Mexico and his text 'The Conquest of Mexico' (1934), - the first play for his Theater of Cruetly, Javier Téllez collaborated with outpatients of the Fray Bernardino Psychiatric Hospital in Mexico City for this film. The patients, who are both co-writers of the script and act as the entire film cast, act in the film as fictional inmates of the hospital and as characters from Mexican history. The ancient ruler Moctezuma appears, along with the conqueror Hernan Cortés and his translator and lover La Malinche, as well as the French poet and playwright Antonin Artaud. Shot in an empty ward of the hospital and the Simón Bolivar Theatre, Xochimilco, Teotihuacan and the pyramids of Cantona, The Conquest of Mexico is a film that obliterates the boundaries between fact and fiction, documentary and story, observation and participation.

Exhibition view:

dOCUMENTA (13), Kassel 2012

Photo: Thomas Strub

Madness is the Language of the Excluded,” An interview with Javier Téllez by Michèle Faguet and Cristóbal Lehyt, C Magazine 92, Toronto, Winter 2006

The interview format is most fitting for a discussion of the recent work of Javier Téllez given that he is so articulate and forthcoming about the complicated set of references—historical, literary, cultural, personal—that have informed his practice. Téllez is earnest in his attempt to engage in an ethical, consequential manner with communities of individuals who live outside of the models of normative behavior that define the parameters of a ‘sane’ society but that are constantly shifting in relation to the ideological structures that determine this social order.

Téllez’s

interest in articulating a position of alterity is partly

autobiographical: both of his parents were practicing psychiatrists in

the provincial city of Valencia, Venezuela. His father, a Spanish

immigrant, was a pioneer in his field and the first to introduce certain

psychotropic treatments in Venezuela. Perhaps his exposure from a very

early age to those deemed mentally ill by the medical establishment

produced a recognition of the process of alterity as a permanent

cultural condition, inscribed within Western epistemological models of

identity based on antagonistic binarisms of self and other.

The

collaborative nature of his work means that the final product presented

in an art context has been determined collectively and is not

necessarily based on the aesthetic considerations we might come to

expect. In this conversation Téllez has described his work as

documentation of fictional scenarios constructed from within the

psychiatric institution from the point of view of those who inhabit it.

What the viewer sees is a work that has no claim to authority, no

centered point of view; it is not easy work but vulnerable and

ambivalent. It is work that demands the viewer’s active participation.

JT:

The museum and the psychiatric hospital are products of the

enlightenment project. It is not a coincidence that ‘la convention’ of

the first republic opened the Louvre to the public in 1793 at the same

time that Philippe Pinel was named chief physician of Bicêtre. It

is as if the same impulse that created the museum liberated the

patients from their chains, marking both the birth of the modern asylum

and the public museum.

Growing

up as the son of two psychiatrists, I often visited the psychiatric

hospital where my father worked. At that time I also began to go to

museums and I remember that even back then I already found a lot of

similarities between both types of institutions: hygienic spaces, long

corridors, enforced silence and the weight of the architecture…Both

institutions are symbolic representations of authority, founded on

taxonomies based on the ‘normal’ and the ‘pathological,’ inclusion and

exclusion.

I

have always been very interested in these ‘other’ museums of the

pathological: the wunderkamern, freak shows, collections of art of the

mentally ill, exhibitions like “Entartete kunst” or “l’art brut,”

because in their morbidity they reveal to us the ‘pathology of the

museum,’ showing precisely that what is excluded from the museum is what

constitutes its very foundation: "El sueño de la razón que produce monstruos." (The sleep of reason that produces monsters)

La Extraccion de la piedra de la locura

(The Cure of Folly), 1996, is my first project that deals with a

specific psychiatric hospital. The installation filled an entire floor

of the Museum of Fine Arts in Caracas, and was intended as an archeology

of the psychiatric institution Barbula, the state hospital where my

father worked all of his life. But it was also a critical reflection on

the museum—the installation was presented as a museum within the museum

and included archival material like a collection of photographs

documenting the life of the institution since its foundation in the late

50s, psychological tests, medications, electro-shock machines, etc. The

installation also contained a selection of artworks made by the

patients. This piece represented my first collaboration with mental

patients and included, for example, a series of piñatas that patients

made especially for the installation shaped after pharmaceutical pills

like Prozac or Valium. The idea was to create a panorama of the

psychiatric institution presenting as many different visions as

possible. Visitors would see an institutional history of treatments

represented in display cases, but would also be given the opportunity to

hear the ‘voice’ of the patients represented in their artworks and the

piñatas. Since then, I have become more interested in this collaboration

with patients. If there is a critique of the mental institution it make

more sense that it be articulated by them.

MF&

CL: Your work has been described as giving visibility to peripheral or

neglected communities or situations. Your collaboration with mental

patients necessarily treads a thin line between representation and

exploitation. How do you negotiate your own position when working with patients?

JT: The

question of ethics is always at the core of representation. Mental

illness only exists within the realm of representation: it is a language

and our task is to challenge it. Most “objective” representations of

the mentally ill have been made by the psychiatric institution, in which

the discourses of the patients are always categorized as mere

illustrations of their diagnoses, not to mention stigmatic media

constructions. The

experience of madness can be situated historically in between the

prohibitions against action and against language; these prohibitions

also involve the representation of the body of the mentally ill,

observed and catalogued only as a representation of the illness.

Fortunately there are also counter discourses articulated by the patients themselves that can be use as models to understand the problem of language. Artists

and writers like Hölderlin, Artaud, Richard Dadd, Adolf Wölfli, Artur

Bispo do Rosario, Louis Wolfson and others have created a language of

rupture that not only questions the conception of madness but also the

fundaments of language itself. These discourses can be used, above all,

as tools for a definition of the ethics of representation of those with