Kamera, osvjetljenje, ritam, zvukovi, muzika... premda sve izgleda kao studentska varijacija začudnih efekata Davida Lyncha, film je strašno dobar.

Još samo da nepodnošljivi Gosling nije bio glavni glumac (iako, srećom, jedva da uopće glumi, a i izgovara samo nekoliko rečenica).

Film je dobio i užasno loše kritike.

Note to critics: Nicolas Winding Refn is your better. If he waves an obstacle at you, do the fucking work and clap. Feedback about his latest contours meek between gossipy foreplay bitching for the sequel to Drive and flat bitching. Only God Forgives is a film static below its need, a dream blood interlude in the loose arena of Refn’s Fear X – the anticlimactic Herbert Selby Jr.-penned pause through cinematographic reds that got his money spanked because America is nothing. Nothing you want to happen will. Fuck your want. Instead, you’re going to loom behind granite and end up on the floor, pissing clay. This movie gnaws you a better head slow enough to care. No payoff tattles itself forced. It goes extinct halfway up its mother – where heroes belong. Moments earn the nut to birth you out again into your same rigidity. The stroll and lack found a stop-motion castration to paint silences, a stoic wampum extreme with wanting spanked. The filler comes between your eyes. Chips a space there at which doctors will shrug. Scenes edit together fat end first. No victory except air. It’s more than floating. I have beheld Gosling, long since proven far above his prettiness, (see him pictured beside our lord and savior Gaspar Noe, whose colors ride here, whose real corpses prop here) dragging someone nowhere by the roof of their mouth. Behold a McCarthy-level police monster improvise someone’s ligaments apart. Jodorowsky wallpapers stiff between militant karaoke, his zodiac trailing us smeared gifts. Continuity don’t mean shit. The incremental no-way parse will be our bread. Aren’t we begging to lose a fight every time art is made? Every time some cocky little shit pops up to weigh in about what makes sense. Every time you form a thought (or refuse to) the punishment for it is already handy. Go into this movie wincing for anemia. Go in ready to lose and return fuller. There’s no shortage of other films now showing that’ll press your stuffing for you into a healthy understanding. We can philanthropically suck ourselves accomplished or go worship the shattered. Oops, if I’m making a point, cut off my fucking neck. I like this person’s art so much I want to use his dick to blow my brains out. - Sean Kilpatrick

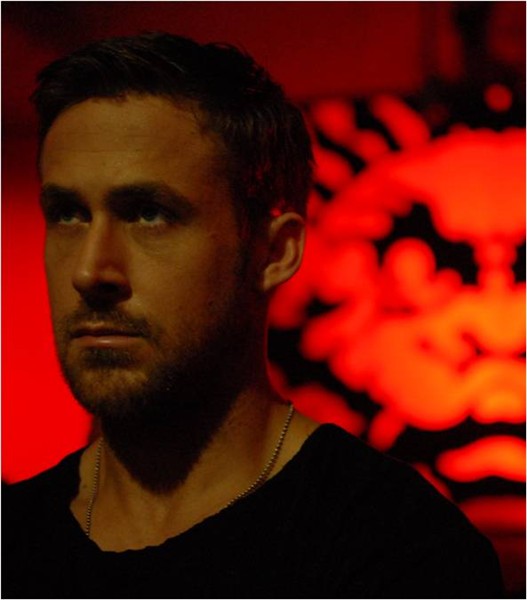

I’m wearing the same expression as Ryan Gosling there: I just saw Only God Forgives, director Nicolas Winding Refn’s followup to Drive. (If you’re in Chicago, it’s playing through Thursday, 1 August at the Music Box; the film is also apparently streaming online.) Actually, I was so impressed I went and saw it twice.

Anyone out there want to chat about it? I’ll post some initial thoughts after the jump. (Beware of serious spoilers, though: these points cover the entire film, and give away key plot points.)

[My capsule review for those who don't want to read the rest: Of the five new films I've seen so far this year, Only God Forgives is easily the most compelling and my favorite. In second place is probably Iron Man 3, which I mostly enjoyed, but found nowhere near as interesting as this. Securely in last place is Star Trek Into Darkness.]

- A lot of people will despise this film because they’ll go in expecting Drive 2: Driven. And while both films share certain aesthetic concerns, Only God Forgives is not another sweet, fun, periodically violent movie like Drive. It is instead consistently and brutally violent, nightmarish, and challengingly abstract. In that regard, it’s more like the “black metal Viking film” that Refn made before Drive, Valhalla Rising. (I wasn’t surprised to learn that Refn wrote OGF before he made Drive.)

- I’ll reiterate that Only God Forgives is very violent movie. Refn refers to both Gaspar Noé and Alejandro Jodorowsky in the credits, which is apt; he’s making a companion piece to their films. David Lynch’s influence is also palpable, especially Blue Velvet, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, and Lost Highway. (Just like Drive, OGF is heavily allusive.)

- But I don’t think that the extremely unnerving violence is why so many people have disliked this one. Many movies are violent. What makes Only God Forgives so consternating is threefold.

- First, unlike with Drive, Only God Forgives is often spatially and temporally disorienting, which will no doubt annoy many people to no end. But Refn (who shot the film in scene order) has very deliberately built this disorientation into the film, and it is precisely these experiments with time and space that provide much of the film’s pleasure.

- The disorientation begins with the all-Thai opening credits, which reminded me of Tarantino’s nod to the Shaw Bros. at the opening of Kill Bill, as well as Jean-Luc Godard’s dedicating Breathless to Monogram Pictures.

- Actually, I was reminded of Breathless repeatedly throughout the movie. Refn, like Godard (and like Seijun Suzuki), is using a familiar gangster story as the basis for exploring various formal issues. As I’ve said elsewhere, if you want to make something radical, it can be a good idea to start with something familiar and deform that. (This is pure Russian Formalism—Refn gets it!)

- Some, however, will think the movie plotless, and its dialogue bad. That would be wrong. Refn has erected the bare minimum of plot and dialogue needed to motivate the movie and keep it going. For instance, the scene where Julian (Ryan Gosling) and Mai (Yayaying Rhatha Phongam) meet Crystal (Kristin Scott Thomas) for dinner, is simple to the point of being comical. But there is no need to make it more plausible. It very elegantly does precisely what it needs to in this film.

- I’ve read an earlier draft of the script (you can find it if you’re willing to stick your arm into the darker corners of the internet), which featured much more expository dialogue—explanations as to who or what the police office Chang is, and further details regarding Julian’s family’s business. And I can’t tell you how happy I am that Refn cut all of that out. In translating the film from script to screen, he removed a lot that was extraneous—not unlike how Rick Rubin helped Kanye West subtract elements from Yeezus.

- This reduction left Refn free to explore other issues, such as cinematic conventions for constructing time and space—not to mention more room for gorgeous shots of people walking slowly from one place to another, their footsteps echoing impossibly loudly. (Point Blank is another clear influence here.)

- Drive was occasionally dreamlike and fantastical, but it remained rooted in a plausible time and place. Only God Forgives lets go and, like Valhalla Rising, functions more as a dream (or a nightmare). The cinematographer, Larry Smith, also shot Eyes Wide Shut, which featured a delightfully fake-looking New York City. Only God Forgives brings the same lack of interest in verisimilitude to Bangkok.

- This delivers us to the second reason why I suspect people haven’t liked the film: the film’s interest in performance, and of being the subject of focused attention. Like Eyes Wide Shut, it features numerous scenes in which a character stands on display in front of an inscrutable crowd. The test of the character is how he or she responds to that attention—how he or she performs.

- For instance, watch the first time we meet Chang (Vithaya Pansringarm). He walks down the alley, then turns to stride toward the hotel where Billy has raped and murdered the prostitute. He is first on display for us, walking toward us. Then, as he approaches the building, he becomes the object of the attention of other characters, who are silently sitting and standing there, bathed by blue and red police lights. But Chang’s stride never falters—he walks steadily, at his own pace, on display but without any reaction to so much attention. And this of course follows a scene where people are gathered to watch a Muay Thai boxing match. As well as several scenes where Billy observes and is observed by prostitutes.

- I remember thinking the first time I saw these scenes: “This whole movie is going to be variations on the strip club scene in Drive, where Gosling’s character threatened the thug with the bullet and the hammer, all while the motionless strippers impassively observed.” And I wasn’t wrong!

- For instance, in what is probably the most harrowing scene in the film, Chang tortures an ex-pat goon in front of his entertainers and others. The film even comments on this concept, as one of the police officers instructs all present: “Remember, girls, whatever happens, keep your eyes closed. And you men…take a good look.” The film well understands what the viewer is feeling: I want to watch, but I don’t want to watch, but I want to watch. (We even get a nod toward one of cinema’s earliest shock moments: Buñuel and Dalí’s Un chien andalou.)

- These scenes of concentrated performance are more often than not the scenes where Refn most distorts time and space. For instance, pay attention to the second sex scene between Julian and Mai, when Julian gets up and reaches through the beaded curtain to touch her. Refn in facts cuts between two different times: in one of them, Julian remains seated on the couch, wearing a black t-shirt; in another, he gets up and touches Mai while wearing a white t-shirt. Two different scenes are being conflated (which might suggest that one—the one where Julian actually does something!—is not really happening). Complicating things further is that Refn then introduces another space: he crosscuts Julian and Mai with shots of Crystal, who is seated on a couch and leering. The montage implies that she’s watching Julian and Mai—but Refn then reveals that Crystal is watching a different sexual performance, featuring muscular young men in thongs.

- Ever since Lev Kuleshov—hell, ever since Edwin S. Porter—cinema’s artists have been exploring the ways that they can construct time and space through montage. In other words, much of the content of Only God Forgives is cinema itself—surely a worthy enough subject for a film?

- Many won’t think so, and as a result, they will think the movie empty, or valueless. J.R. Jones, for instance, writing in the Chicago Reader, complains in his review that the film’s “fascination with extreme gore never amounts to more than a fetish, and there’s none of the deft characterization that made [Refn's] revered Pusher trilogy and British biopic Bronson so engaging.” How to respond to such a shallow reading?

- For starters, the fetishism that Jones so quickly dismisses comprises the very heart of Only God Forgives, which is fascinated with fetishes (surely another worthy subject for the cinema?). Understanding and accepting this proves crucial to grasping the deft characterization so thoroughly on display, but that Jones has not eyes to see. The film’s central narrative is Julian’s growing fascination with Chang, and the power that that supernatural force of a man embodies—literally embodies, in his all-powerful right sword arm. Julian initially thinks himself powerful, the owner of a boxing arena and school, but the film steadily dispels him of that illusion. Note, for instance, the film’s contrasting of Julian with the Muay Thai statue, very early on. Julian’s attempt to form fists proves feeble. Later, during Julian’s fight with Chang, Refn match cuts between Chang and the Muay Thai statue, demonstrating who really possesses that power.

- Once you see this aspect of the film, you see that it’s stuffed with the “deft characterization” that Jones desires. The first sex scene between Julian and Mai, for instance, provides numerous clues to Julian’s psychology. Mai ties to him to a chair and proceeds to masturbate as he observes. Julian then senses the presence of Chang and gets up (he has magically become untied) to explore blood-red corridors until he arrives before a door as ominously black as any door in a David Lynch film. (Actually, an older precedent can be found in the hallway scene in the cosmetics factory in Marc Robson and Val Lewton’s The Seventh Victim, as well as in the mirror that leads between worlds in Jean Cocteau’s Orphée.) Julian tentatively reaches his right arm into the void, only to have it get lopped off by Chang just as Mai reaches orgasm. (There’s a free term paper on vagina dentata waiting to be written there.)

- Julian craves power, and sexual satisfaction, but he fears humiliation—but he also craves humiliation. These issues are inextricably intertwined for him; note how his mother’s humiliations of him are always sexual. Above all else, Julian (who is impotent?) craves potence, and the film details his discovery and exploration of a power greater than his own.

- This gets to the third reason why this film will probably displease many viewers: Gosling is playing the exact opposite of the strong silent type he portrayed in Drive. Julian is instead a weak silent man—a coward and a momma’s boy who’s only reward is betrayal and abuse—and who nonetheless keeps coming back for more! (Did Guy Maddin direct this?)

- Note how, after Julian dons the three-piece suit for his dinner date with his mother, he keeps it on for the rest of the film. (Mai, of course, gets out right away, and later abandons Julian, after he’s been thoroughly beaten by Chang.) Note also how Julian’s various black and white outfits are variations on Chang’s unchanging black-and-white suit, while everyone else wears reds and blues and yellows.

- Most importantly, note how Julian ultimately realizes and accepts that the only thing that will satisfy him is humiliation and, eventually, castration at the hands of a foreigner. In other words, Julian finds the fulfillment he’s looking for. The film’s ending is actually a happy one!

- There’s your engaging and deft characterization, J.R. Jones—though I doubt you’ll enjoy it.

- (Has anyone out there read Paul Bowles’s “A Distant Episode“?)

Well, I’ll no doubt have more to say about the movie later, but for now…what are your own thoughts? - AD Jameson

CANNES – Refn, whose criminal drama “Drive” won him the Prix de la mise en scène (Best Director) at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival, followed up this year with his second film with Gosling, a visionary thriller shot in Bangkok and titled “Only God Forgives.” The film, perhaps the biggest disappointment of the festival so far, dramatically divided the critics into two camps. Some argue that Refn’s new production is merely a replay of “Drive,” only this time the plot has been diluted by beautiful photography (an opinion BLOUIN ARTINFO shares). Others retort though that unlike most of the competition titles that seem popularist, Refn’s film convincingly embodies the very concept of auteurism.

In the production, two American brothers run a boxing club in downtown Bangkok as a cover for drug-smuggling. The older sibling, Billy (Tom Burke), has been murdered at a local brothel for raping and killing a 16-year old prostitute. The brothers’ menacing mother (Kristin Scott Thomas cast against type but simply excellent in the role of a sinister matriarch) flies in to town and demands that the younger brother, the fierce and uptight Julian (Ryan Gosling), avenge the killing. One of the key characters of this excessively violent story is an enigmatic Thai police officer named Chang (Vithaya Pansringarm), who seems to materialize out of thin air right at the scene of crime – he is the one to decide who is gong to live and who is going to die, enacting some Karmic justice with the help of a samurai sword that he carries tucked under the back of his shirt.

It is Chang — an evil fatum (“fate”) of an ancient tragedy incarnated – who never fails to mete out the punishment that Julian’s mother and Julian himself have to confront. To expand on the ancient Greek metaphor, Chang is also the choir of an ancient tragedy: the most violent scenes of “Only God Forgives” are cut in such a way as to be juxtaposed with Chang’s karaoke interludes in front of an entire police unit, set against the background of fake plastic flowers.

Although the film has received mixed reviews as to its relative merits, it seems nearly impossible to take a well-argued categorical stand here. Refn speaks the cinematic idiom flawlessly, but he employs it to articulate his own idiosyncratic concerns and anxieties: “Only God Forgives” looks as if the director was methodically transferring to the screen his most intimate nightmares and dreams. It is a sequence of confident fantasies, that occasionally congeal into tableaux vivants or burst into gushes of blood: every shot is meticulously thought through and executed: nothing is left to chance.

A directors’ interview shown in which he confessed to having been obsessed with this dream-project of a movie long before “Drive” came along, came as no surprise: Refn says that despite an avalanche of interesting job offers after the release of “Drive,” he could not resist the script. With an oriental backdrop, persistent allusions to ancient mythology and obvious passion towards the genre (as well as a deeply personal element) converge on the screen to become a picture so enthralled with itself, that it overwhelms and tramples down the viewer.

Refn’s latest production may be quite boring for most viewers, where “Drive” was infinitely more watchable and enjoyable for showing genuine concern for the audience, “Only God Forgives” serve as an unabashed playground for the director’s ambitions. Perhaps from the point of view of the proverbial Karmic justice, it is hard to deny that Refn deserves the right to play out his directorial ambitions the way he sees fit. - Nailya Golman

Michael C from Serious Film here to report on one of my most anticipated titles of 2013 while Nathaniel is away.

So at this point any write up of the film needs to address two questions. Not only, “Is Only God Forgives really that bad?” but also “What is it about this particular films that has sent so many reviewers around the bend?” [more...]

The short answers are, “Yes. It is god awful.” and “Because a breathtaking amount of skill has been applied in making this piece of cinematic excrement.” There is something about such supreme talent used in service of this reprehensible material that snaps something in the critical mind and turns thoughtful, mild-mannered critics into a version of Gosling from Drive’s elevator scene, insanity in their eyes, stomping away long after their target is dead.

Lest you think Only God Forgives is being unfairly persecuted by a bunch of hothouse flowers who swoon at the sight of blood. I have liked or loved every film Refn has put out so far, going so far as to declare Drive the best film of 2011. I am loathed to join in a critical dog pile and would have enjoyed nothing more than to report back that the conventional wisdom is wrong, and that the film is a masterwork being unfairly maligned by small-minded reactionaries.

But, oh, such hopes do not survive long into the viewing of Only God Forgives. This film is garbage. Exquisitely mounted, gracefully assembled garbage. It is often argued that any art that provokes a strong reaction is doing something right, but I wouldn’t even grant this film that much credit. There is no value to be found in this film, not even in hating it.

I will at least say this for Only God Forgives: It has made me appreciate Drive all the more. Remember the scene in Drive where Bryan Cranston is killed? How even in that moment of shocking violence there was humanity in the way Albert Brooks eased his friend into death as gently as possible? For all its bloodshed that was a film stocked with human beings.

There are no human beings to be found in Only God Forgives. Only meat bags, useful as far as they can be posed in bullshit macho scenarios and then eviscerated. The film opens with child prostitution, rape, bludgeoning, and mutilation and that is only warm up for the various stabbings, beatings, scaldings, and eye gougings that follow. I should point out that any of these things I’ve listed can be redeemed in the execution. Context matters. Here they are thrown out haphazardly, in the hopes that the potency of the violence will obscure the fact that the film has not a thought in its head, nor any viewpoint on the material beyond “Isn’t this cool?”

If you think this sounds like the building blocks of a potentially interesting story don’t be fooled. Any semblance of intrigue is buried under a slag heap of artsy neon “atmosphere” and student film level stabs at David Lynch surrealism. At least a third of the film can be categorized as dead air.

One

might be tempted to watch for the potential fun of seeing Kristin Scott

Thomas play her toxic gargoyle of a character like she’s trying to

out-camp Bette Davis’s performance in Baby Jane, but nope, you

would be wrong there too. She has no impact at all, spouting one-note

awfulness in scene after scene, devoid of context or character. As for

Gosling, to say he crosses the line into self-parody is a generous

understatement. He makes his character in Drive seem downright

chatty by comparison, spending the bulk of this film staring at the

world in mute blankness. Out of utter boredom I began counting the

number of words Gosling actually speaks in the film, and topped out at

108, which I believe puts him neck and neck with Karloff in Bride of Frankenstein.

One

might be tempted to watch for the potential fun of seeing Kristin Scott

Thomas play her toxic gargoyle of a character like she’s trying to

out-camp Bette Davis’s performance in Baby Jane, but nope, you

would be wrong there too. She has no impact at all, spouting one-note

awfulness in scene after scene, devoid of context or character. As for

Gosling, to say he crosses the line into self-parody is a generous

understatement. He makes his character in Drive seem downright

chatty by comparison, spending the bulk of this film staring at the

world in mute blankness. Out of utter boredom I began counting the

number of words Gosling actually speaks in the film, and topped out at

108, which I believe puts him neck and neck with Karloff in Bride of Frankenstein.I cannot begin to explain what went wrong here. Both Refn and Gosling have proven themselves valuable artists in the past but after this they need to do some serious soul-searching to figure out how they were capable of leading each other hand in hand into such a cesspool. I am tempted to bump the film up to a D- in deference to Larry Smith’s gorgeous cinematography and Cliff Martinez’s terrific score, but nothing can detract from the repugnance on display. When someone serves you shit on a silver platter, you don’t compliment the shiny tray. Only God Forgives is without question one of the worst movies I have ever seen. - thefilmexperience.net/

Nicolas Winding Refn says he made Only God Forgives 'like a pornographer'

Drive director confesses to a fetish for violence, and star Kristin Scott Thomas says film became 'more and more despicable'

Acting of violence ...

Kristin Scott Thomas and Nicolas Winding Refn talk about Only God

Forgives at the Cannes film festival. Photograph: Ian Gavan/Getty Images

Two sounds provided the keynote of the first screening of Nicolas Winding Refn's

follow-up to Drive: the screams of characters being subjected to

grotesque acts of dismemberment and torture, and the slap of seats

springing upright as members of the press walked out of the grandest

cinema at the Cannes film festival. One American woman exclaimed loudly as she exited: "This is shit."

Even its British co-star, Kristin Scott Thomas, said: "Films where this kind of violence happens I don't enjoy watching at all" and joked that as the film was made "it got more and more despicable". But its director, Nicolas Winding Refn, said that he approached filmmaking "like a pornographer: it's about what arouses me. Certain things turn me on more than other stuff and I can't suppress that." He added: "I have surely a fetish for violent emotions and images."

Only God Forgives, which reunites Winding Refn with Drive star Ryan Gosling, is the first great schismatic movie at Cannes, with critics either panning its violence or dazzled by its stylised brilliance – or else wildly vacillating between the two positions.

Challenged on the film's violence, Winding Refn said: "Well, art is an act of violence. It is about penetration, about speaking to our subconscious and our moods at different levels."

He added: "I don't consider myself a very violent man … but I have surely a fetish for violent emotions and images and I just can't explain where it comes from. But I do believe it's a way to exorcise various things. Let's not forget that humans were created very violent: our body parts are created for violence, it is our instinctual need to survive. But over the years we no longer need violence but we still have an urge from when we are born – which itself can be an act of violence."

Set in a Thai underground world of fight clubs, prostitutes and seedy American crooks, it is a visual feast, with little dialogue and the Wagner-influenced score taking a prominent role – more in harmony with the director's earlier, more recherché work than the commercial hit that was Drive.

It stars Ryan Gosling as owner of a Bangkok boxing club, and Scott Thomas as his mother. She is a peroxided Clytemnestra of a character – trashy, American and emphatically nothing like the cut-glass-accented aristocrats she is most famous for playing. She had given such roles a "kick in the teeth" with this part, she said.

At one point she is required to say a deeply offensive and misogynist phrase that Gosling told Winding Refn was "the worst thing you can say to a woman in America". She struggled with the line ("cum dumpster"). "It took me about eight takes to pronounce the words", she said. Asked by Winding Refn if she would repeat it there and then, she said, "No."

According to Winding Refn, Scott Thomas "had no problem turning on the bitch witch". She added: "It wasn't like I need to find a part that means I can break the terrible shell I have been trapped in: it wasn't like that at all. It was more organic than that. Every day we would get braver.

"When I first read the script I was excited about playing someone far away from the upper-class thing that English people seem to love seeing me in. As we got nearer it got more and more despicable."

Even its British co-star, Kristin Scott Thomas, said: "Films where this kind of violence happens I don't enjoy watching at all" and joked that as the film was made "it got more and more despicable". But its director, Nicolas Winding Refn, said that he approached filmmaking "like a pornographer: it's about what arouses me. Certain things turn me on more than other stuff and I can't suppress that." He added: "I have surely a fetish for violent emotions and images."

Only God Forgives, which reunites Winding Refn with Drive star Ryan Gosling, is the first great schismatic movie at Cannes, with critics either panning its violence or dazzled by its stylised brilliance – or else wildly vacillating between the two positions.

Challenged on the film's violence, Winding Refn said: "Well, art is an act of violence. It is about penetration, about speaking to our subconscious and our moods at different levels."

He added: "I don't consider myself a very violent man … but I have surely a fetish for violent emotions and images and I just can't explain where it comes from. But I do believe it's a way to exorcise various things. Let's not forget that humans were created very violent: our body parts are created for violence, it is our instinctual need to survive. But over the years we no longer need violence but we still have an urge from when we are born – which itself can be an act of violence."

Set in a Thai underground world of fight clubs, prostitutes and seedy American crooks, it is a visual feast, with little dialogue and the Wagner-influenced score taking a prominent role – more in harmony with the director's earlier, more recherché work than the commercial hit that was Drive.

It stars Ryan Gosling as owner of a Bangkok boxing club, and Scott Thomas as his mother. She is a peroxided Clytemnestra of a character – trashy, American and emphatically nothing like the cut-glass-accented aristocrats she is most famous for playing. She had given such roles a "kick in the teeth" with this part, she said.

At one point she is required to say a deeply offensive and misogynist phrase that Gosling told Winding Refn was "the worst thing you can say to a woman in America". She struggled with the line ("cum dumpster"). "It took me about eight takes to pronounce the words", she said. Asked by Winding Refn if she would repeat it there and then, she said, "No."

According to Winding Refn, Scott Thomas "had no problem turning on the bitch witch". She added: "It wasn't like I need to find a part that means I can break the terrible shell I have been trapped in: it wasn't like that at all. It was more organic than that. Every day we would get braver.

"When I first read the script I was excited about playing someone far away from the upper-class thing that English people seem to love seeing me in. As we got nearer it got more and more despicable."

Bangkok Dangerous: Nicolas Winding Refn on Only God Forgives

by Brandon Harris

A superviolent and supremely strange Bangkok nocturne,Only God Forgives is Nicolas Winding Refn’s follow-up to his Cannes award-winning pop culture sensation Drive. This film, sure to be nowhere near as popular, is a distinctly less accessible affair. One senses that the filmmaker, a born contrarian, takes a certain pleasure in this.

In both Thai and English, it meditates on a white man who trains child fighters and runs a family-operated drug ring with his brother. When said brother is dispatched via some brutal south Asian justice involving really sharp swords (after he is found to have rapped and killed a teenage prostitute), our Western family is torn between those that want to seek revenge and those that don’t. Featuring another taciturn performance from Ryan Gosling, a career-altering, Lady MacBethian turn by Kristin Scott Thomas and one of the more affecting (and effective) no name newcomer discoveries of recent memory in the form of Vithaya Pansringarm, who plays the local constable bent on foiling Thomas and Gosling’s mother-son revenge plot, the film is a candy-colored kaleidoscope, a mythic piece of near camp, a brutal new entry in Refn’s undeniably fascinating filmography.

The 42-year-old Refn, who was raised between Copenhagen and New York City, cut his teeth making low-budget crime thrillers in his native Denmark. For over a decade, he was most notable for his Pusher trilogy, the first of which was recently remade in English. He gained increased international notoriety with his 2008 biopic Bronson and 2009 medieval Norse action flickValhalla Rising, but it wasn’t until the international success of 2011′s Drive that he was vaulted into the top tier of international auteurs. Only God Forgives bowed at this year’s Cannes to great derision and controversy. It opens Stateside via RADiUS-TWC today.

Nicolas Winding Refn

Filmmaker: Despite the rape and murder and general sense of violent excess that one finds throughout this picture, I actually found it quite funny, almost campy. Did you think it was important for the film to have some levity?

Refn: I think the film needed comedic moments. I wanted moments of humor because that would only underscore all the other fetish qualities the film would have. If Drive was like cocaine, I wanted this film to be like acid. Good taste is the enemy of great art.

Filmmaker: When you talk about being a fetish filmmaker, what exactly is one supposed to find in this film that links it to the others and your own predilections and predispositions?

Refn: It’s not like I have a list I want to check off of want I want to do or not do. I approach it like a fetish because if I don’t, I would spend too much time thinking about whether something was the right thing to do or not. I saw the whole thing like a pin-up magazine. Every frame has its specific function. It’s only when you have flipped through the whole movie, or the whole magazine, that all pieces will add up. I have to ask myself, what would arouse me? It’s almost like taking off your clothes in front of an audience and indulging in your deepest desires despite the consequences. It’s a great creative outlet. To me, filmmaking is not about the result, it’s about the process. Finding ways to make that process purely an act of expression and not a consequential thought process and a series of reactions.

Filmmaker: What drew you to Bangkok initially?

Refn: Thailand is a very popular spot to vacation for Scandinavians. The first time we went to Thailand it was my wife and I. We went to Bangkok and really liked the city. We went back with our children. We experienced the whole beach world of Thailand. It was fantastic. We started coming regularly, every year, and we always made a point to stay over in Bangkok for two different reasons. My wife had one reason and I had another reason. I began to become interested in what it would be like to make a movie there. So I think the initial spark was what would it be like making a film in Bangkok.

Filmmaker: Fairy tales and myths have always been an important source of inspiration for you. Were they this time around?

Refn: It’s a combination of many things. It has a very different language than Drive. Part of it was to make a crime drama in this very different part of the world that was a bit of a haven, and yet Westerners are living in exile. They’ll never be part of Thailand for real and yet they cannot leave Thailand. The idea of strangers in a strange land is very dramatic. Surroundings are foreign to you and yet you live within it. So the idea of a crime family and the head of the crime family being a woman. I think especially as Americans this is sort of a taboo or an unusual idea.

Then I had this idea of including a fight gym in this. One night in Scotland I was bored and I started looking at my clinched fist. I thought, “God this is a classic image from a fight movie.” All it is really is just the consequential symbol of male masculinity and male sexuality. When I opened my fist, my palm, it was like the ultimate submission. I thought that was an interesting trick. Then this idea of a mythological figure within Bangkok, a classic sheriff, almost as if I was making a Western, where there are people causing trouble in the city and the sheriff has to restore order. I really wanted him to come out of Thai mythology, however. I was going to shoot the entire movie by night, and by night Bangkok becomes this very mysterious, mystical landscape. It was pure Thai in its aesthetic and its mindset. The spiritual world and the world of reality coexist. It’s very intoxicating. So it’s the combination of all of those elements, that was the movie becoming what it was.

Filmmaker: When we chatted about Drive a few years back, you spoke about going to L.A. and wanting to have a classic Hollywood director’s experience. So you got a house in the Hollywood Hills, you took meetings and gave notes in offices on studio lots, you actively sought to live a myth of what L.A. filmmaking is all about. Was there a way in which the experience of going and making a film in Thailand offered a similar emersion in a exotic kind of working style being a European director?

Refn: I think the idea of doing Drive as a pure, romanticized L.A. thing — coming to Los Angeles, living in the Hollywood Hills, working on movies, being a foreigner, making the kinds of films you make within the dream factory — it’s a fairy tale itself. In Bangkok, the idea of making a supernatural movie from an Asian point of view was intoxicating. I felt like a stranger in a strange land making the film. I had to remove all of my Westernized logic and sense of law to understand and experience a completely different mindset.

In the end, when we came to Bangkok, my daughter, youngest of four, can see ghosts. We knew ever since she was born. We came to Bangkok when she was two. Once you realize your children have this ability to see ghosts, it’s really something. In Bangkok, we were living in a haunted apartment. She’d wake me up four or five times every night pointing at the walls screaming, “No!” Something was trying to communicate with her. It was very annoying, very tiring. In the end, I had to call the production manager and be like, “There’s a ghost in the apartment. What can we do?” And she, accepting that experience, coming over with a shaman, quenching the apartment, realizing that their were spirits here, it wasn’t a dangerous spirit but it was very annoying to my daughter because it kept trying to communicate with her. It had latched onto us since we’d gotten to Bangkok. For us, it was truly a contest. At the same time, realizing the acceptance within that culture of the spiritual realm right alongside the acceptance of the iPhone and the Internet, both at equal levels was what the movie had to become.

I wanted to create a tableau of a mother-and-son relationship. The need to confront his mother manifests itself through a third person who is one part supernatural force and one part real. A bit like my own experience with my daughter’s abilities. Accepting that there are two levels of reality.

Filmmaker: What about Ryan Gosling’s silent visage are you particularly drawn to? You get these remarkably evocative performance out of him that are nearly wordless.

Refn: He has this incredible ability to say a thousand words without dialogue. That’s such a good canvas to work with. For this film, the whole design of a man being chained to the rule of his mother, it’s almost as if his mother has put a spell on him, so he’s like a sleepwalker. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, that sort of thing, the mythology of the sleepwalker, caught between worlds, the desire for his mother and the repulsive attitude toward his mother. He hates her, he loves her, he wants to have sex with her, he’s repulsed by her. It’s a very primal attitude between all men and their mothers, whether we like it or not.

Filmmaker: Kristin Scott Thomas had never done anything remotely like this. What gave you the impression that she could do it?

Refn: Because of my budget, I had to clear any celebrity casting. I had no one originally in mind. We were looking for anyone who had all the aspects the character needed. In the end the casting director suggested we try KST. I was like, “Yeah, might as well,” so I sent the script to her and she responded by wanting to read it and talk about it and then we met in Paris. I had a certain perception of her, of what kind of actress she is going in which is still there. Yet in the course of out dinner I realized that she’d have no problem going where I needed her to go. So after dinner we sort of agreed that we should go on this journey together. She made a big point to suggest that if she were going to do this, she would want to transform herself into something completely different.

What’s great about an actress like KST is she has the ability and the craftsmanship to go anywhere at any given time so we spent a lot of time in prep making the character organic and designing her. Once we started, she was like in complete Crystal mode. A lot of that for an actress involves this physical transformation and that’s why it was so important for her to completely transform every part of her body for this character whether it was the tanning of her skin, to her nails, to her hair, to her makeup, her wardrobe, that’s how they really transform. The dragon had revealed itself. - filmmakermagazine.com/

“ONLY GOD FORGIVES” DIRECTOR NICOLAS WINDING REFN ON THE CREATIVE FREEDOM THAT COMES WITH MAKING DIVISIVE ART

BY: DAN SOLOMON

The director of Drive and Only God Forgives talks about making art on your own terms and the inspiring films of . . . Michael Bay?in

“There were many cheers. There were many boos. It’s no difference to me,” Nicolas Winding Refn says while sitting next to his composer, Cliff Martinez, in a back booth at Midnight Cowboy in Austin. It’s a Friday afternoon, and the filmmaker is in town to promote Only God Forgives, his follow-up to the 2011 surprise hit Drive. The reason he’s in Austin to talk about the movie is because it’s been selected as part of the “Drafthouse Recommends” program that the Austin-based Alamo Drafthouse theater chain started this summer to generate positive word-of-mouth about movies that the chain’s management thinks deserve the extra attention--and Only God Forgives could certainly use some good word-of-mouth after its Cannes premiere made international headlines for being booed at its first screening.

So Refn is playing it cool, explaining that the boos meant nothing to him, that he wore them like a badge of honor, that he knew he wasn’t making another Drive, and anyone who expected he was is the one who’s confused here.

Although that film, which also starred Ryan Gosling as a taciturn, violent man who walks a thin line between dreamlike unreality and brutal hyperreality, didn’t necessarily win over all audiences either. While many rated Drive the best film of 2011, famously, one woman filed a lawsuitagainst the movie theater that sold her the ticket for “having very little driving in the motion picture.” All of which leads to an interesting question for Refn: If you’ve been sued by your audience and booed by your critics, and you’re still out there making movies, you’ve already experienced the worst case scenario for most filmmakers. And once you’ve lived through the worst, are you free to do whatever you want?

It’s an idea that seems to appeal to Refn. He talks about the creative freedom that comes with making art without a concern for pleasing his audience in rapturous terms. “I’ve lived on the border of financial destruction for the last 20 years, because the sheer joy of doing something your way is--you can’t define it,” he says. “It’s like heroin.”

Here are some of the creative lessons that Refn has learned as a result of his willingness to make divisive art.

EVERYBODY CARES ABOUT WHAT THE AUDIENCE THINKS--BUT YOU CAN’T LET THAT DEFINE YOUR PROCESS.

Refn may appreciate the rush he gets from fully indulging in his creative freedom, but that doesn’t mean that the Danish director doesn’t have feelings. Even when he talks about the boos he received at Cannes, he’s quick to point out that there were others in the crowd--like, presumably,The Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw, who gave the film a 5-star review immediately following the festival--who cheered at the end.

“Every time that you express something, you have to prepare yourself for critique,” Refn says. “It’s not like critique is a nice thing to get. We all don’t want to be yelled at for doing something wrong. But you begin to look athow people are critiquing, and it becomes interesting. So when people are violently reacting to an experience that you have given them at the same time that people are praising or loving it for the exact same thing--that’s when you know you have done something right.”

Most artists are sensitive by nature, and sensitive people are inclined to hear the voices of their critics much more clearly than the voices of the people who praise them. For Refn, the key is to hear both the people who love you and the people who hate you as a combined sound that signifies artistic validation. “It makes them think,” he says. “It makes them react. Art was not made to satisfy the masses in any way, and it never has.”

DON’T TRY TO GIVE PEOPLE WHAT YOU THINK THEY WANT.

“When you make something that’s extremely successfully financially, or with an audience, there’s the expectation that now you’ve got to do that again,” Refn says. But as the type of artist who uses the term the masses to describe an audience, he’s not inclined to find that even remotely interesting. “That puts you in a prison, because you can’t do that again. You can do a version of it; you can imitate it; you can do similar things, which can be terrific and very satisfying in a way, but I just don’t respond to that.”

When Refn looks to controversial art for inspiration, there are a few names he keeps in mind--he refers to David Lynch as David--but he seems most proud when he talks about Lou Reed’s controversial album Metal Machine Music, which the Rolling Stone Record Guide described in 1979 as “a two-disc set consisting of nothing more than ear-wrecking electronic sludge, guaranteed to clear any room of humans in record time.”

“We talk a little bit about the Lou Reed album Transformer, and then his next album, Metal Machine Music,” Refn says. “I think every film I make is the Metal Machine, because every time I’ve made a film, people have always said, Why didn’t you do what you did the last time?”

FEEL FREE TO CONTRADICT YOURSELF.

A few minutes after explaining that art shouldn’t cater to the masses’ demands, Refn says, “I do believe art is for the masses, for sure.” He also talks about other heroes he has as a filmmaker--and when he’s pressed on whether David Lynch tops that list, he veers sharply in the other direction.

“I’m a huge Michael Bay fan,” Refn declares, perhaps in jest, perhaps not. “I think The Rock is a really well-conceived film. I think technically, it’s incredibly inspiring. Those Transformers movies are just incredible. I have a lot of respect for Michael Bay.”

It’s not exactly what you’d expect to hear from a guy whose latest film takes one of the most handsome actors in the world and puts his bruised, beaten, puffy face on its poster--but declaring your affection for a similarly critically reviled icon of the mainstream is also kind of a counterculture move. At the very least, part of following your own muse is being as willing to disappoint your high-art fans as you are those who came to see you at the multiplex. So how does Refn really feel about the big Hollywood blockbuster?

“I would love one day to make a Michael Bay movie,” he says. “That would be a lot of fun.”

MAKE SURE THAT WHAT YOU’RE DOING SATISFIES YOURSELF, AND THE REST WILL FOLLOW.

Drive was a critical and financial hit. Refn’s previous film, Valhalla Rising,grossed just $30,000 in the United States, which made Drive’s $77 million something of a lightning-in-a-bottle moment. But Refn had no expectations for that film’s success, which allows him to keep those expectations in check for Only God Forgives. “Drive was never devised as anything but my next movie,” he says. “Things just become different from day to day. It frees yourself from the expectation of what you did, so now when you make a new film, it’s a blank slate.”

Ultimately, for Refn, the key to creative freedom is simply chasing his own interests and passions wherever they take him--and if that results in making a film that’s hated by as many critics as love it, that’s a trade-off he’s willing to make. “There is a great satisfaction in people cheering and booing at the same time,” he says finally. “Then you know that you are the Sex Pistols.”

Nicolas Winding Refn Talks ONLY GOD FORGIVES, Confirms Horror/Thriller I WALK WITH THE DEAD As His Next Film; Contemplating Tokyo Setting

by Adam Chitwood

We were all big, big fans of director Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive here at Collider last year, so it’s with eager eyes that we’ve been watching Refn’s follow-up, Only God Forgives, unfold. The film stars Ryan Gosling as a man who’s been living in exile in Bangkok for the past ten years after killing a cop. He manages a Thai boxing club as a front for a drugs operation and finds himself in hot water after his brother is killed for murdering a prostitute. The boys’ mother arrives in Bangkok to collect her son’s body and instructs Gosling to take revenge and “raise hell.”

Refn recently spoke a bit about the making of the film and even touched on his next project, a horror movie/sex thriller called I Walk with the Dead starring Carey Mulligan. Hit the jump to see what he had to say.

Speaking at length with the French outletLiberation (translated by the trusty The Playlist), Refn addressed the casting change that occurred when Luke Evans dropped out of the lead role and elaborated on the tone he’s set for the pic:

Speaking at length with the French outletLiberation (translated by the trusty The Playlist), Refn addressed the casting change that occurred when Luke Evans dropped out of the lead role and elaborated on the tone he’s set for the pic:“From the beginning, I had the idea of a thriller produced as a western, all in the Far East, and with a modern cowboy hero. I was lucky, Ryan Gosling has accepted the role when Luke Evans withdrew. He preferred to star Peter Jackson‘s The Hobbit…Luke Evans’ agent has probably done him a great service.”

Refn also talked about his filming process, saying that he shoots largely in chronological order and prefers to shoot on the fly rather than rely on storyboards:

“I hate the idea that the film is over before we started shooting… I spent whole nights finding places in Bangkok. Especially in Chinatown, where most of the film unfolds. We saw dozens of nightclubs, each more kitsch than each other, the walls covered with carved paneling, thick velvet, with flowers in colored plastic gueulardes, erotic statues or classic gold…they give me ideas for scenes.”

Finally, the director confirmed that I Walk with the Dead will be his next film, and he’s already secured financing. He describes it as a horror movie and says, “We’ll turn to Los Angeles or Tokyo.” Personally I’m hoping Refn takes on a Tokyo setting for his next flick; I love the idea of infusing Refn’s style into a new location for each film. Not much is known about the plot, but Refn previously said the project came about because he always wanted to “make a movie with lots of sex.” So, expect lots of horror-infused uglies bumpin’ I guess. He’ll reunite with his Drive cohort Carey Mulligan on the flick, but no production start date has been set.

Finally, the director confirmed that I Walk with the Dead will be his next film, and he’s already secured financing. He describes it as a horror movie and says, “We’ll turn to Los Angeles or Tokyo.” Personally I’m hoping Refn takes on a Tokyo setting for his next flick; I love the idea of infusing Refn’s style into a new location for each film. Not much is known about the plot, but Refn previously said the project came about because he always wanted to “make a movie with lots of sex.” So, expect lots of horror-infused uglies bumpin’ I guess. He’ll reunite with his Drive cohort Carey Mulligan on the flick, but no production start date has been set.

Given that he’s still shooting Only God Forgives, it may be late this year or early 2013 before cameras start rolling. After that, hopefully he and Gosling will get moving on that Logan’s Runremake. If there’s something I want to see more than a Refn crime thriller in Bankok, it’s a Refn sci-fi movie.

Only God Forgives, as A.D. Jameson’s excellent 25-Point Post claims, is a great pleasure to watch and to think and talk about. And in this post (which owes much to A.D’s) I want to talk a bit about how the movie deals and centers in Xenophobia, Racism and, by far most interestingly and vitally, Sexism.

The movie’s extreme Xenophobia and Racism are quite obvious and need little explanation outside of how they reinforce the more interesting and varied Sexism that controls and overwhelms this great movie.

The extreme Sexism that the movie traffics in and wields about quite beautifully and, to some extent, flagrantly, is, indeed, something of a complicated beast. And looking at a large slice of the female side of the coin of this movie one might believe that women are its soul, its dream, its ghostly pleasure-force and feel reassured that such captivating and transfiguring elements are able to maintain a kind of independent and alternative sort of power.

But, this would be wrong, because in its decisive moments and passages, the female’s mysterious and seemingly impenetrable masturbatory pleasure and dream-stage-lushness is turned and co-opted, by the male-God force of the movie, into sheer, show-stopping violence. (and, in fact, some of the dreamy staged females are men. How many? Half? Who knows?)

The most obvious “fight” or “war” staged in Only God Forgives is that of the sexes personified through Chang, Godlike Thai local, and Crystal, Julian’s Godlike, avenging monstrous mother. And this “fight” creates some tension, for a while, shaping up into a decent sort of contest–but after the botched hit (on Chang) Crystal admits that she has lost and all that’s left for her to do, really, is stand up against the window glass and take it in the throat.

Crystal—a real monster, caricatured, nasty, smart, powerful, unlikable and disgusting—is a decent foil for Chang, Thai Godlike Hero, and makes a splashy impact on us, the audience, by humiliating her son (like the hotel reception “girl”), and creeping us out with the way she touches him—insinuating quite unnatural abominations. And Julian, (the character one might expect to be the hero) is really just, as AD Jameson says, “a momma’s boy” who can’t measure up against the irresistible local God (Chang). He’s just in the movie I think to underscore a kind of Western weakness that submits, ultimately, to the Thai hero. (and of course he’s played by Ryan Gosling).

All the foreigners (Westerners) in this movie are bad/weak/evil. They are corrupting the local culture with their drugs, and abusing and sometimes killing the local women. And they need to be (and are) punished. When Julian surrenders to his destiny, the failed Westerner, it makes for a neat and inevitable ending. Like shoelaces being tied.

The less obvious but more interesting and crucial “fight” or “war” in this movie, though, involves what seems like solid female territory. Territory that the female seems to dominate, carving out and laying claim to a vital sort of rival energy, separate and inviolate, to the male violence. And this other fight that I’m talking about here takes place in the arena of “performance.” In fact the battle doesn’t just take place in the arena of “performance” it is a battle for “performance.” A battle for the shows of the movie.

The show of Mai masturbating, privately for Julian, and then, staged, in front of a live audience behind just a glow-beaded curtain; the lavish show and set in which the most savage and discomforting violence takes place (“the most harrowing scene in the film,” to use A.D. Jameson’s language), a dreamy, lush oasis: an alternate world in which the stars are the women. And the movie gains real tension and much of its power by way of these shows, these sorts of dreamy and trippy, masturbation-worlds which pretend and almost attain a kind of ghostly, ethereal and undefeated soul (of the movie) revolving around and centered in Mai, Julian’s paid love interest.

One might (and should) argue that these stages, these “sets,” are run and masterminded by men. But, then, again, one could retort that the soul of these stages, these sets, is still the women, the area between Mai’s legs, the look on Mai’s transfigured, blurred face (and more, in Mai, herself) and that this “soul” is able to float about vital and uncorrupted by the movie’s savage male forces.

And that would be nice. Yes, it would be nice to claim vagina dentata power for the female (per A.D. Jameson, again, here) but the blade is Chang’s and Mai just kind of fades out (they could have been more cruel about this, but that would have been a mistake) and the lush, incredible set where the harrowing torture scene takes place is filled with hidden knives that Chang can simply tiptoe among and pluck out quite whimsically, almost comically, and completely insidiously. The female landscapes and soul of the movie are, basically, just a harbor for male weaponry placed there and reclaimed as needed.

At the end of the day the performance and dream soul world of the movie doesn’t just get used by men it centers in and is constituted of and by men. The first time we see Chang singing on stage in front of his henchmen it’s kind of weird, creepy, discomfiting, but when this happens near the movie’s end it is a coronation and consummation, a post-coital sort of glow, stamp, seal and assertion (coitus here as the preceding ultra violence).

Our Godlike, Thai male, Chang, doesn’t just take over the female performance stages for his carefully choreographed shows of violence he also, in the aftermath, becomes a tender (and extremely creepy) singer performing to his rapt, transfixed henchmen. It is a total male victory. And it is extremely disturbing.

- Rauan Klassnik

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar